Doing Geology

Excerpt from Stories in Geology: What we Know and How We Figured It Out by G. Dolphin (2016)

Epistemological Trajectories: Deconstructing Methods, Resolving Controversies

Geologic Practice: Knowledge and Interpretation

T H I N K Q U E S T I O N

What is at the heart of inquiry in the geosciences?

The accounts in this book make it abundantly clear that the development of knowledge in the geosciences was not a smooth process. Knowledge did not logically build, one argument on another, in a straight and obvious line, a predetermined path that essentially led to the understandings and information we have today. You know now that even if textbooks often portray science as a rational and linear path of discovery, this is far from the case in real life. The controversies you have read about would never have happened if scientific advancement was as easy as formulating a hypothesis and testing it experimentally for a pass/fail result—with the “true” side merely conducting a test to “prove” its fidelity or “disprove” the alternate view. As you have learned, developing knowledge in geology (and other sciences) is about developing a story that best explains the observational data.

Trying to understand what geologists actually do and how they approach doing it takes some understanding of what it is they are studying. Since geology is the study of the earth, its materials and phenomena, investigations are usually field-based. This study thus involves actually observing the earths’ surface, materials, and phenomena. Fieldwork typically requires a geologist to go to an area and look at the bedrock cropping out there. Geologists identify rock types and structures to determine the history of the area; they describe the area and the sequence of events to explain why the area looks the way it does. Darwin made many contributions to both biology and geology from his work on the HMS Beagle, traveling to many different locations. Mary Anning made great contributions to the burgeoning discipline of paleontology with her methodological extraction of fossils from the cli s near her hometown. Willima Smith used his job building canals to create the First geologic map. Edna Plumstead strengthened the explanatory power of continental drift with her work in the field on Glossopteris fossils.

It is noteworthy, however, that not all geology occurs in the field. Often, the finer details of the rocks cannot be accurately observed in the field. In this case, the geologist collects representative samples to take back to the lab for further study. He or she may use a microscope to characterize things like mineral assemblage, mineral grain or crystal structure, or biological structures of fossilized organisms. She may be interested in finding the age of minerals in the rock, in which case she uses an analytic device that isolates elements and measures their presence compared to others. He may wish to understand the pressure and temperature conditions responsible for the formation of the particular suite of minerals and thus may use equipment to expose samples to very high temper and pressure to observe their reactions.

These kinds of experiments allow the researcher to revisit determinations of the history of the earth, what happened when (description), and why or how (explanation). Further, models and modelling, as we will discuss, are of course also important in geology. As earlier chapters have shown, the scale of space and time for many of the earth’s phenomena are very large—too large for reasonable study in or out of the lab. For this reason, many geologists use models or make assumptions about the phenomena to develop approximations of how the phenomena work. With these generalizations and assumptions, there will necessarily come disagreement, controversies. This should also be clear from the narratives in the book.

Resolving Controversies: Historical and Experimental Science

As we discussed in the first few chapters, as a history of the earth began to develop, there was a shift from textual information (such as the Bible) to observations of the natural world. Steno observed crosscutting relationships in layered rocks to infer a history of the areas around Tuscany. Murchison, de la Beche, Lyell, Phillips, and others used field observations to develop the geologic time scale. Cuvier pieced together a history of the Paris Basin using fossils and other signs in the rocks at that location. Analyzing the earth to develop an understanding of its history would become the practice of geology. Therefore, geology is a historical science, alongside evolutionary biology and cosmology. This generally contrasts with disciplines like physics and chemistry, which are considered experimental sciences, because knowledge is developed by designing experiments in the present while controlling and observing the appropriate variables. Certainly, geologists do perform experiments—plenty of them—but the data they generate still go towards generalizations about past phenomena; again, the story of what happened and why.

Since the phenomena affecting the materials and structures of the earth occurred in the past (when no one was around to observe them), today’s geologists, like those in the past, are forced to look at the evidence resulting from such phenomena and interpret the cause. This is a different process than actually observing a particular phenomenon; further, it has implications for how we construct knowledge about these past events. Interpretation is the process of developing “a story,” based on the observational data. The best interpretation is the one with the best explanatory power to make sense of the data. It then becomes the one that scientists ultimately build consensus around. It becomes the answer until new data arise calling for a different story, or an even better way of looking at the old data is found.

Think of Section III and the earth dynamics problem: Why do we have continents and ocean basins? Frankel (2012) describes the three strategies for knowledge development within a controversy:

- Each group (mobilists, fixists, expansionists) tries to develop and continually improve the idea that they think best addresses the data.

- They attack or “poke holes” (point out weaknesses) in the rival group’s explanations, decreasing its explanatory power. It is up to the rival group, then, to address the weaknesses by showing how their idea does address the weaknesses.

- The group compares and demonstrates that their story is superior at explaining the data.

These strategies are especially visible during the controversy between the horizontal displacement explanation for oceans and continents and the thermal contraction explanation. In the end, however, no one knows for sure what happened in the past, since no one was around to witness it. Geologists ultimately build consensus around the idea with the best explanatory power. This becomes the answer until new data arise calling for a different story, or a better way at looking at the old data is found.

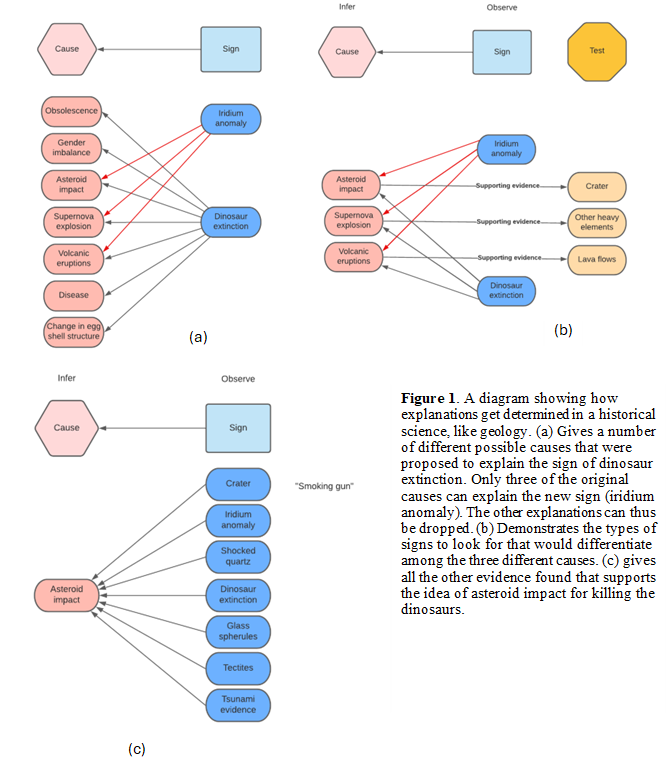

An example of this process at work is evident in our developing understanding of how the dinosaurs became extinct. While we have covered this already, it bears repeating in this context (in a condensed fashion). Paleontologists (scientists who study [-ologist] + ancient [paleo-] life) observed that dinosaurs were the dominant life form on earth for some 160 million years—a very long time indeed. Yet, at about 65 million years ago, all of them suddenly ceased to exist. Many hypotheses were proposed to explain this observation and paleontologists tried to build a case for each to determine which was the best candidate. Clearly, some of the processes (and associated theories) were likely to provide more discoverable traces than others:

A sickness or disease that affected all dinosaurs. The difficulty with the disease or epidemic theory is that finding evidence for such a microorganism would prove to be difficult, if not impossible. Without evidence, it is hard to support this hypothesis. A rapidly changing climate. We can interpret climate change in a region from a change in flora and fauna. Evidence for such a change at the right time could then lend support to the idea.

A global environmental disaster of some sort. Any global catastrophe, like massive volcanic eruptions, would also leave signs of its occurrence. One need only to look in the correct places to see them. Global disaster can be demonstrated with the appropriate evidential support.

Some kind of astronomical event with a global impact (like a super nova explosion). It turns out that even the super nova could leave discoverable signs on the earth. These signs would be in the form of certain heavy elements, iridium for example, that get blasted into space, enter the earth’s atmosphere, and settle out with other dust and dirt, creating sedimentary deposits on the earth’s surface. Such evidence could support this hypothesis.

Gender imbalance due to a warming climate. Warmer temperature could have affected the ratio of males to females by determining the sex of a developing egg. This would be a very difficult idea to find support for, as determining sex from the fossilized skeleton (or fragments of a skeleton) is not an easy task.

In the late 1970s, Walter Alvarez and his team of geologists, who were at work on another problem, found a layer of sediment (a sign of a past phenomenon) containing a much higher concentration of the element iridium (a possible clue to the nature of the phenomenon) than normally occurs at the earth’s surface. The team’s task was then to discern the cause of the anomaly. They found that a high iridium layer in the sediment could be caused by three things:

- Fallout from a nearby super nova explosion

- Massive volcanism, as iridium is found in higher concentrations in the earth’s mantle

- An asteroid impact—iridium is also found in high concentrations in any extraterrestrial objects, which includes meteoroids and asteroids

They had to narrow the choices—which assumes there was only one cause, something not necessarily the case. To narrow down the prime cause (and the associated hypothesis) of the iridium anomaly, they searched for other signs that would be left by each of the three phenomena. This is similar to testing the hypothesis but does not usually involve setting up an experiment (When you are talking about a mass extinction, it is probably best not to pursue some kind of experiment). If a super nova explosion occurred, several other heavy elements besides iridium should be found in the clay layer. With massive volcanic eruptions, we should have evidence of large lava flows. An asteroid impact means we would expect an impact crater. Keep in mind, however, that lack of a crater or the lack of extreme lava flows do not constitute a failed test of the hypothesis. Not finding either of these might simply mean that the researchers have not looked in the correct place to find such signs, or the sign(s) have been obscured or destroyed from surficial processes like weathering and erosion (Figure 1).

The point is, in experimental science the researcher makes a hypothesis and then devises an experiment to test the hypothesis and determine reliability. In a historical science, hypothesis testing is much different: in essence, the experiment has already been run— since the origin of the earth. But no variables have been controlled either. We are left only with the signs of multiple causes complicated by infinite intervening contingencies. It is like showing up at a crime scene after hundreds of people have already passed through, unwittingly changing, contaminating, or destroying the evidence. Like a forensic scientist, we are trying to piece together what happened. There is no proving what happened, only supporting one possible cause over another, based on supportive data. Diverse groups may look at the same data and develop different ideas for causation, which is both common and normal.

Doing Geology by the Numbers

T H I N K Q U E S T I O N

What is the role of numerical (that is, quantitative) data compared to more descriptive (that is, qualitative) data in geological investigations? Discuss any perceived differences in reliability or validity of the different kinds of data.

Think about the difference between the claims of people like James Hutton, Charles Lyell, and Charles Darwin concerning the age of the earth, as compared to people like Comte du Buffon, Edward Lhwyd, and Lord Kelvin. If you remember, Hutton used observations of weathering and erosion of old Roman walls, along with stream beds on his property, to try and understand the age of the earth. He hypothesized that with such little observable wasting going on over months and years, the signs he saw of “previous worlds” (which had been produced and destroyed in similar fashion) would mean that the earth had to be extremely old. In fact, he stated the earth had “no vestige of a past, no prospect of an end.” In essence, Hutton saw the earth as eternal, although he did not try to put a number on that age. Likewise, Darwin, using his ideas of evolution and natural selection as an explanation for the change in existing species from past to present, declared that the evolutionary process was necessarily slow. It would take the time of multiple subsequent generations, each reacting to environmental pressures, to give rise to a new species. Because the Flora and fauna had changed so much from earlier in the fossil record to what was present during his lifetime, he hypothesized a very old earth. In fact, he needed an old earth to allow for evolutionary processes to have enough time to develop the lifeforms present in his time.

How does their approach differ from those of Lhwyd and others? Remember, Edward Lhwyd used the number of big boulders in a glacially eroded valley to estimate the age of the earth by multiplying an approximate “boulder fall rate” with the number of boulders in the valley. Comte du Buffon heated metal spheres of different diameters and timed how long they each took to cool down. He then took this data and extrapolated it to assess how long it would take an earth-sized iron sphere (his proxy for the earth) to cool—through this extrapolation he proposed an age of the earth. Kelvin refined these estimates, and using the laws of thermodynamics that he had developed, he also calculated an age for the earth. Kelvin supported these calculations with quantitative data from other related aspects of the earth and sun. He used the oblate shape of the earth and the energy released from the sun to claim the earth was no more than 20 million years old. Many other geologists used generalized sedimentation rates and sedimentary rock thicknesses to estimate the age of the earth. In all these cases, the numbers were important because they relied on math, an emergent tool for determining the age of the earth.

Using numbers, physicists claimed as untenable Wegener’s proposals that continental drift could be caused by the force from the earth’s rotation or from tidal forces. Nevertheless, making measurements of the natural world allowed us to develop a much more reliable understanding of how it works. Being able to measure ocean depths—first by sounding with a weight at the end of a long rope, then by sonar, and finally by satellites measuring gravity—allowed us to “see” the structures of the ocean floor. Scientists found that familiarization with seafloor structures was necessary for understanding the dynamics of the planet. Quantifying remanent magnetic forces in iron-bearing rocks in the seafloor and measuring the amount of parent and daughter elements of radioactive isotopes to calculate an absolute age of rocks, also played a major role in our developing understanding of the earth. Combining the two pieces of data allowed us to quantify the spreading rate of different rifting systems.

Finally, measuring earthquakes allowed us to pinpoint their location of origin (hypocenter), outlining the areas of severe crustal stress. Using the seismic data, along with digital analysis and imaging, also gave us a window into the earth’s interior, which we now describe as layered, mostly solid, but with some liquid. As well, it maintains narrow plumes of very hot mantle material that is convecting (that is, the warmer material moves up and the cooler material sinks down) and allowing the earth to cool off. This convective process could also be driving deformation in the skin of the earth, the lithosphere, as the currents move different regions of lithosphere laterally in independent directions.

Q U I C K A C T I V I T Y 1

It is often thought that measurements—the numbers—are more reliable, more objective than a written or spoken description of a place. Why do you suppose that is? What are some possible limitations of relying too heavily on numbers? Are there times in a scientific investigation when quantitative data are not appropriate? Support your answer.

Reliability: Idealized Conceptions vs Reality

T H I N K Q U E S T I O N

Quantitative data, the kind noted in the section above, are often used in, or derived from, mathematical equations. Equations like those in the second law of thermodynamics allowed Lord Kelvin to calculate a value for the age of the earth. Other investigators developed ratios of sedimentation rates against large packages of sedimentary rock or calculated the cooling rates of iron spheres of different diameters against an iron sphere the size of the earth. Equations are one mode of representing reality, one kind of model. Besides these mathematical models, what other kinds of models are there and why might we use them?

When you hear the word, “model,” what do you think of? A small train travelling around a miniature landscape? Catwalks and the world of high fashion? Models, in the scientific sense, have to do with ideas that scientists develop to help describe or explain phenomena in nature. The ideas are developed in the mind and reflect how we understand aspects of the natural world. The specific knowledge or concepts are not, in themselves, reality—they are merely constructs that shape understanding of reality. Because the natural world is exceedingly complex, to understand things about it scientists simplify and generalize about the salient aspects. This is the model-building process, and almost all science is done in this way. For example, weather forecasting is based on computer models, which are simplifications of the atmosphere. The behaviour of a dropped apple is modelled—simplified—as equations that describe things like the velocity, the energy, the mass, and the forces related to that falling apple.

If you open up a science textbook (or, pretty much any science textbook except this one), you will find nestled somewhere in the beginning chapters, a section on how science is done, or some other information about the nature of science. Within this section, you will also come across a rendition of what is commonly called the scientific method. This method is probably something that you have learned about and have had to memorize as the way science is done, the way to develop scientific knowledge. As a refresher, it goes something like this:

Step 1 – Make some observations about the natural world.

Step 2 – Develop a question regarding those questions.

Step 3 – Do some background research on the problem.

Step 4 – Create a hypothesis and make some predictions.

Step 5 – Test the hypothesis using a controlled experiment.

Step 6 – If the test fails, discard the hypothesis. If not, continue to test.

As we have already seen from the examples given above, there is so much more to the process of science than this very linear strategy. The reality is that most scientific papers are written with this type of format to get to the findings as quickly as possible. However, science rarely, if ever, occurs in such a way. Hopefully, this has become abundantly clear to you as you have read earlier portions of this book. If you have been taught The Scientific Method in your prior schooling, please forget it now. It will not be on the test. J The popularity of the scientific method is a result of our idealized conception of what science is and how it works. Allchin (2013) stated that “We want science to be logical. We want science to be progressive. We want observation to be independent of theoretical perspective. It makes the task of justifying and interpreting scientific knowledge much easier” (p. 6). Having read about the successful advancements of particular scientific ideas in the previous chapters, you should now be aware of the many different paths to scientific understanding. A more accurate approach to explaining how science works can be found here: http://undsci.berkeley.edu/article/scienceflowchart

Q U I C K A C T I V I T Y 2

Follow the story of “Asteroids and Dinosaurs” as outlined in the process of science flowchart at this UC Berkley site: http://undsci.berkeley.edu/article/0_0_0/alvarez_01 Then pick another development in geological knowledge outlined in the text and see if you can trace a path along its development on the same flowchart.

We look to a more idealized notion of what science is—what we think it should be—because we are interested in understanding the truth about the natural world. It turns out that even with the many possibilities for error, from assumptions made, to personal biases (which we will be covering shortly), to political, economic, and social influences on the scientific process, it still works really well. The fact that you are reading this book right now is a testament to that. What we seek, through all the possible influences that could lead scientific inquiries awry, are reliable explanations and descriptions. If we make predictions based on an explanation we have formulated from the evidence, do they bear out over time? If they do, then we can assume we are on the right track. If not, we must amend the description or explanation to better our chances at prediction.

Most times, we must shore up our original idea, like adding the concept of isthmian links to the idea of fixed continents to solve the problem of finding fossils of the same organisms on widely separated continents. Recall Frankel’s strategies to explain the factions in a scientific controversy: strengthening one’s theory, showing that the opponent’s theory has weaknesses, and demonstrating that one’s own theory is superior. When critics pointed out that fixed continents did not account for the fossil evidence (strategy 2), fixists went ahead and developed a consistent idea, land bridges or isthmian links (strategy 1).

I N F O D U M P: M O D E L S I N S C I E N C E

In addition to simplifying the natural world, models also have other characteristics that are important to understand. Gilbert and Watt-Ireton (2003) described the characteristics of models used in earth science:

- Simplified. Only certain aspects of the natural world considered to be important to the phenomenon in questions are included in the model of that phenomenon.

- Utilitarian. Models are developed to be useful in some way—to predict or forecast future events, or to explain current or past ones. Scientists often use models as a starting point for investigations into related phenomena. For example, doctors will start with the ideas promoted by germ theory (a model for how micro-organisms affect our health) when trying to discern the cause of illness in a patient.

- Artificial. Models are constructs of the human mind—they are not the real-world object or phenomenon.

- Interpreted. Models are products of the human mind and therefore subject to interpretation by other human minds. Thus, not all people will derive the same meaning from the model as the person who developed it.

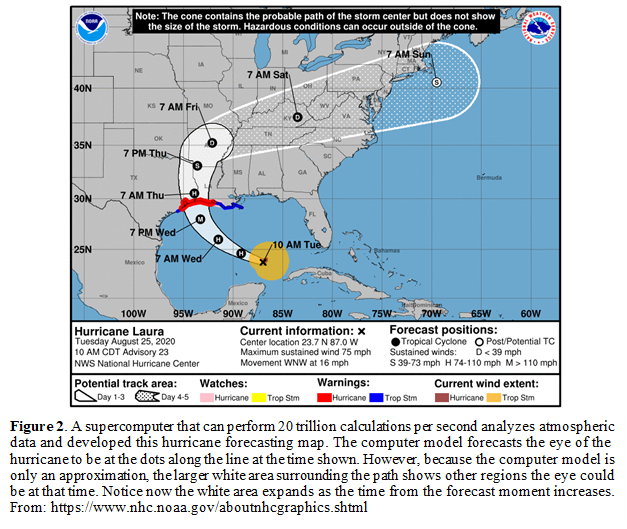

- Imperfect. Since models are constructed by the mind and are simplified tools for understanding; thus, they don’t represent the natural world 100% accurately, although they are good approximations. Scientists study the natural world in greater detail to further refine the imperfections in the model. Despite how refined our computer models for the atmosphere are, for example, and the computer capacity for about 20 trillion calculations per second, we still can only forecast the weather with any degree of certainty for about three to five days into the future (Figure 2).

Models exist in various modes, or types of representation, which Boulter and Buckley (2000) detail in their typology (below). Becoming familiar with these model expressions will allow you to identify different models more easily, and also to notice when they’re used, what they’re used for, and what their strengths and limitations are. From most concrete to most abstract mode, here is how they line up:

- Concrete. These are models that you can hold in your hand. They are three-dimensional objects to represent either the function or the appearance of something in the natural world.

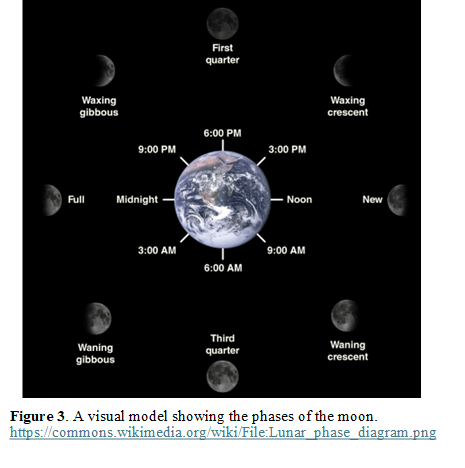

- Concrete functional: These models work in a similar way to the systems they represent and have only a superficial or visual likeness to that system, if at all. For example, this link shows a model of the phases of the moon https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wz01pTvuMa0

- Concrete scale: These models look quite similar the systems they represent, only proportionally bigger or smaller. However, they seldom function like the systems they represent because the properties of the systems do not proportionally scale up or down.

- Visual. These models are two-dimensional representations based on the natural world. They include illustrations, diagrams, concept maps, and so on, such as a diagram showing phases of the moon (Figure 3). Note: Just because you can see the model, does not make it a visual model.

- Gestural. We enact these models with our bodies by behaving in a way that represents part of the natural world, such as one person walking around (revolving around) another, to represent the moon revolving around the earth.

- Verbal. These models are expressed through the written or spoken word. They often take one of the following forms:

- Analogies: A verbal relationship following the form of A:B = C:D. (e.g., Sun:Moon = projector:movie screen)

- Similes: A verbal comparison between the model and target, using words such as “like” or “as.” (e.g., The moon is like a beacon in the night)

- Metaphors: A direct verbal relationship between something that is very familiar to the user and something that is less familiar. (e.g., the earth’s pale companion)

- Mathematical. These models are equations showing relationships between and among different variables (e.g. Fgrav = (G x MMoon • MEarth) / R2)

It is important to note here that because models are simplified, imperfect, and interpreted, they do not give the whole picture of reality. In fact, models highlight certain aspects of reality and hide other aspects, which is their purpose. For instance, the Mercator projection of the world highlights the continents, the oceans, and the orthogonal attitude of latitude and longitude (see Figure 2.18 in Chapter 2). However, it hides the true shape of the earth, and the relative sizes of the continents —for example, Greenland looks to be about three times the size of Brazil but is actually one quarter its size. Understanding what a model highlights, and especially what it hides, is important for understanding the portion of reality that the model represents. This means it is important to see many different models and different modes of the same concept. It gives a more robust picture of the portion of reality that the models represent.

Q U I C K A C T I V I T Y 3

To see what a concrete model is like, make a scale model of the earth moon system using different sports balls, such as a basketball, soccer ball, volleyball, soft ball, baseball, racquetball, or ping-pong ball (all at regulation size). Find two balls whose diameters would, to scale, represent the diameters of the earth and the moon, respectively. Then calculate the distance they would have to be apart if they were to represent to the same scale the distance between the earth and moon in real life.

Q U I C K A C T I V I T Y 4

All examples of the different modes of models are focused on the sun, moon, and earth system. Make a table that describes what each of the models highlights about aspects of the moon and the earth, and what each of them hides. A range of possible answers exist here, but try to develop your table to show the most obvious aspects.

[Need Table Image!!]

Developing Reliable Scientific Knowledge

Sometimes achieving reliability requires jettisoning a whole series of ideas, like porous earth, contracting earth, and expanding earth. It means changing to a whole new contextual explanation, like horizontal displacement. Another example of this is leaving behind the notion that the earth is eternal/timeless, or static/unchanging. Or, that it had no history and that humans had witnessed the earth since its beginning. Instead, these ideas were replaced with the idea that the earth has a history and that humans were very late on the scene for that history.

Serendipity and Interwoven Threads

Another possibility for achieving reliability is when ideas that originally competed, get combined—holding on to the reliable “bits” and eliminating aspects that are not so reliable. For instance, both uniformitarianism and catastrophism had truths within them. Certainly, for much of the earth’s history, change happened in a slow, barely perceptible pace. Yet, there were and are large-scale events (earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanism, bolide impacts). Today, actualism reflects a blending of the two competing ideas—this view recognizes that a long time-span accommodates slow, steady change, but it also accepts that more intense events are responsible for some of that change as well. These newer ideas replaced the older ideas because they answered two aspects of the data (Thagard, 2012):

- The broad aspect, in that they addressed data over a wide selection of phenomena. For instance, the idea of a very old earth addresses a broad range of observations, such as our understanding of the rate of weathering at the earth’s surface, evolution, and the rate of mountain building and other tectonic forces.

- The deep aspect, in the pieces of an explanation can be seen as mechanisms, or expressions of more fundamental explanations. For instance, plate tectonics explains many of the observations we make about the origin of mountains, but plate motion becomes an expression of a deeper, more fundamental plume theory.

Serendipity is a chance occurrence—putting together otherwise non-related thoughts, witnessing an unexpected phenomenon, an unlikely chain of events—that leads to scientific knowledge gains. We like to think that science results from mostly rational thought, planning, and experiments with controlled variables. However, as should be clear from the stories in the previous text, chance happenings are very much an important part of the scientific endeavour. In other cases, a person might bring together two or more ideas and ponder what would happen if they pursued that combination.

Q U I C K A C T I V I T Y 5

As you can see now, science often does not follow the predictable linear trajectory. Try to identify examples of scientific knowledge development in the preceding chapters that DID NOT follow this process. Give a brief outline of the process that did happen.

Such a case of weaving together previously unrelated insights happened in the 1860s when James Clerk Maxwell (1831–1879) synthesized his understandings of both magnetism and electric currents and developed his theory of the electromagnetic field. This development laid the groundwork for future advancements in quantum mechanics and relativity. As was discussed in Chapter 7, Fred Vine and Drummond Matthews (and Lawrence Morley, independently) put together the ideas of continental drift, seafloor spreading, and the magnetic anomalies on the seafloor to develop the idea of plate tectonics. Robert Dietz then took that idea and combined it with Arthur Holmes’ mantle convection and Wilson’s plume theory to create an explanation for plate motion. In many instances, a scientist with specific past experiences and insights could have been pursuing something for a particular purpose and through a series of unpredictable circumstances, an unexpected event or outcome occurred. This then informs how we today understand an aspect of the world. Here are some other examples:

- John Harrison spent the better part of his life in the early 1700s developing a clock that could keep time on a ship that is always rocking on the waves, and where there are wide variations in temperature, humidity, and salt. While his motivation to invent technology came from a desire to make life easier for a particular group of people in a particular time and place, by producing this clock, he also produced ball bearings and the bi-metallic strip. They, of course, have wide application in industry more generally, and have led to new insights about the natural world.

- Mary Anning became famous because her chance childhood find of a Plesiosaur fossil intersected with her dad showing her the importance of the “formed stones” (fossils), and how to clean and sell them.

- Alfred Wegener, while looking at a map at his neighbour’s house, recognized a similarity between the west coast of Africa and the east coast of South America—giving rise to his idea that they were once attached to each other and later broke apart.

- Antoine Henri Becquerel by chance placed a piece of pitchblende on photosensitive paper and found that this rock radiated energy that exposed the paper.

- William Henry Perkin, an English chemist during the 1840s and 50s, was trying to develop an antidote for malaria, and accidentally developed a dye of the colour mauve during his mixing of different chemicals. This was the first synthetic dye —and so was very cheap to make—and rapidly became very popular, making a fortune for Perkin.

- Walter Alvarez and his group were not looking for an iridium anomaly in the Italian clay layer, but were investigating a change in single-celled marine organisms. This chance discovery ultimately led to the development of the impact theory of dinosaur extinction.

The list goes on. Where much of science is about refining ideas, testing them under different circumstances, we must always acknowledge the role of serendipity, of chance. This includes both the chance happening, but also the past experiences and insights that may transfer into a new situation or arise from linking ideas that had no prior association.

Scientific Laws and Theories

In general, then, scientists build models based on the data and then test them to measure their reliability. Sometimes these models are derived from descriptions of the natural world. The most reliable of these descriptive models in science we call Scientific Laws, and they usually take the form of mathematical equations. They offer no explanation of how or why something happens, like the acceleration of a dropped apple. They merely state that given a set of circumstances, or variables, we can substitute measurements in for the variables and calculate (predict or forecast) an outcome.

Other models are explanatory in nature. The most reliable models, or groups of these kinds of models, gain the designation of Scientific Theories. Scientific theories explain why something happens the way it does. Based on what a given explanation implies, scientists can make predictions about the natural world and then test them, allowing a measure of reliability for the theory. Darwin’s theory of evolution allowed us to know which age of rocks would likely yield intermediate forms of life that could bridge related fossils. When scientists looked at such sites they found what was expected. With the development of genetics and the ability to identify specific genes, we have verified both broadly and deeply Darwin’s (and Alfred Russel Wallace’s) theory for descent with modification. Despite the problems brought up in the previous section about plume theory, current research seems to be verifying that idea. In other words, the observations we should be making about a convecting mantle, we are indeed finding.

It is common for those same authors who perpetuate the idea of the scientific method as outlined above, to claim that hypotheses become theories once they have been tested and when scientists are “pretty sure” about their veracity. They then assert that once a theory has been tested successfully, time and time again, it becomes a law; that scientific laws are more trustworthy than scientific theories. This is not at all accurate. Scientific laws and scientific theories are constructs that perform different functions (describe and explain, respectively), and one does not evolve into the other. This will never happen. This misguided thinking also reinforces the colloquial definition of “theory,” that is, it is only a pretty good guess. Again, this could not be further from the truth. Scientific theories occupy the same top rung of scientific surety as do scientific laws. They have both been tested and achieve unsurpassed support from observational data made by the scientific community. Simply put, they are the most reliable way to describe natural phenomena.

Having just said this, I will note that despite their seemingly clear and differentiated definitions, the deployment of these terms—Law and Theory—is a messy business. For science, both terms are used to designate very reliable models. To complicate matters, however, it is also common for scientists to talk about inductive reasoning as “creating theory” or “theorizing.” These ideas certainly do not hold the same stature as “true theories,” which have years of evidential support. Wegener’s idea for horizontal displacement of the continents is most often referred to as Wegener’s theory of continental drift, though others have referred to it as Wegener’s hypothesis. There is no hard and fast divide that delineates when a hypothesis becomes a theory. Instead of worrying about this, one should always check to see how an idea has held up to scrutiny. If it has faced many challenges and scientists continue to use it, if it continues to be reliable, then that should be sufficient, regardless of how one might refer to it.

Assumptions in the Scientific Process

T H I N K Q U E S T I O N

An important aspect of doing science is the role of assumptions in the development of knowledge. Select three different individuals or episodes covered so far where assumptions about the natural world played a key role in understanding that part of the natural world. Based on the specific instances you describe, what is the advantage to the scientific process of making and relying on assumptions? What do we need to be wary of when making these assumptions?

Just as scientists develop and use models to support their understanding of the natural world, they also make assumptions, which similarly simplify systems and aid in their investigations. However, when scientists “take for granted” common understandings—such as how an aspect of the natural world works or that a model faithfully behaves like the natural world—they make assumptions that may not, in fact, reflect what really goes on.

The Impact of Assumptions: An Example

Both Edmund Halley and John Joly assumed that summing the amount of dissolved salts going into the oceans from rivers—relative to a measurement of the total salt in the ocean —would make it possible for them to calculate the age of the earth.

T H I N K Q U E S T I O N

What other assumptions are part of the approach taken by Halley and Joly? How reasonable are each of them?

Halley and Joly’s method was founded on the assumption that measuring just the influx of dissolved salts from the main rivers into the oceans would the give total influx. However, other questions are pertinent here:

- Is it possible that other inputs exist?

- What about all the small rivers, creeks, and streams that also flow into the oceans?

- What about groundwater flow into the oceans?

- Are there are inputs deep on the ocean floor that these investigators did not know about?

- What is the effect of oceanic biology on the amount of dissolved salts in the ocean?

Other geologists looked at the rate of sedimentation and the thickness of sedimentary rocks, from the earliest ones to modern day, to determine the age of the earth.

[Insert Table Image!!!!]

Note how the difference in just two assumptions (maximum sediment thickness and rate of deposition) can lead to such vastly different calculations (3 million years to 1.5 billion years). We should also consider other assumptions Halley and Joly made. One pertinent assumption concerns what happens to the lower sediments in a thick stack of sands and muds as more sediments pile up on top. The answer is that compression and loss of volume occur, which will affect the total thickness. Then, do all sediments compress the same? The answer here is that they do not. For instance, clay deposits start out with about 90% porosity, but can compress to a point where little space remains between grains. Sands and gravels, on the other hand could be deposited with a porosity as high as 30%, depending on sorting. This means that if the sands and gravels experience enough pressure, they can lose this porosity, thus decreasing their volume by up to 30%. Probably, however, because of the round shape and hardness of the grains, the loss of volume would be much less.

Is deposition something that takes place constantly? Well, in some cases it does, like in the deep sea, where a constant rain of fine sediments occurs. The possibility of the quick emplacement of thick sequences of sediments also exists—called turbidity flows—caused by the occasional storm or earthquake. How might geologists account for this? They also need to decide how to assess places where sedimentation is intermittent. This can be complicated because if sedimentation was not happening during a particular period, it becomes difficult to determine how much time passed before sedimentation resumed.

Another confounding factor comes from those places where sediments experienced an erosional event. When such processes remove a thickness of sediment or rock, not only do we not know the amount of time erased, but we do not know the amount of time between erosion and deposition. So, how can we know the amount of time in that sequence of sediments, from which we then calculate a sedimentation rate?

Foundational Assumptions

All of these complexities would make a task such as determining the age of the earth seemingly impossible. To alleviate such notions of impossibility and complexity, scientists turn to simplifications, like the models we have already touched on, and, of course, assumptions. Assumptions have limitations, as the above examples make clear. This is especially true when approaching fieldwork with preconceived notions—assumptions that inherently bias both what an investigator considers data and how that data will be interpreted. Realizing this problem, many early geologists promoted the idea of entering the field with multiple working hypotheses (MWH). In practical terms, this meant the geologist would consider many different interpretations for particular field observations, and would test them individually in the field. Ultimately, the geologist would settle on the one working hypothesis best supported by the data. Although this was the gold standard through the 19th century (at least in North American geology), a careful review of historical controversies and arguments reveals that many geologists did not use the MWH approach (Greene, 2015).

The important insight here is that the enterprise of science starts with assumptions. In general, to do science, you need to hold to the following foundational assumptions:

- The causes of phenomena that we observe are natural and mechanistic.

- The existence and influence of these natural causes is consistent throughout the natural world.

- Systematic study of these phenomena helps us to understand these natural causes.

These foundational assumptions ( http://undsci.berkeley.edu/article/basic_assumptions ), are not “provable” however. Still, they are the necessary starting point, the context within which we assess our observations when trying to develop scientific understanding of the natural world. The reason geologists have done this successfully is by not concentrating in particular on the knowledge they develop or whether that knowledge represents some external, reality-based “truth.” Instead, they concentrate on the reliability of the descriptions and explanations they develop, to make predictions that ultimately bear out.

For instance, we could believe that the current configuration of continents and oceans exists because an all-powerful being emerging from a universal ocean, pulled up some mud from the bottom of that ocean, and spread it unevenly across the ocean surface, thus creating high spots and low spots. We could also believe the earth’s crust is composed of two different density materials and that the less dense material sits up a bit higher (continents) and the denser material sits a bit lower (ocean basin). How do we decide between them? If we want a scientific answer to the question, then we must discount the first choice; this is because we start from an assumption that phenomena in the natural world have natural causes. We do not consider an all-powerful being to be natural. We can then make observations of the natural world, aiming to discern the mechanistic causes of the phenomena we observe, which in turn will generate descriptions or explanations. These become the basis for predictions, which further observations are intended to verify. If the observations do not bear out the predictions, we clearly need to modify the earlier description or explanation. On the other hand, if the observations support the predictions, this clarified understanding persists until we develop an even better answer. In science, we keep the answers to inquiry only as long as they are reliable.

Understanding this process is essential to appreciating science and scientific knowledge claims. Although we strive to reflect the reality of the natural world in our scientific laws and theories (and there are many who think this is the case), we can never absolutely know that reality. In fact, most of our scientific “truths” of the past have been discarded because a new knowledge claim had greater reliability than the original. Therefore, what we need to look to is the reliability, justifiability, or evidential support of our knowledge claims, and take for granted that the more reliable the knowledge claim, the closer to reality it is. The idea of not knowing reality makes some uncomfortable about the veracity of science. How can we have faith in an institution if the very pillars of its existence, the knowledge it generates, is likely to change? However, keeping in mind these two generalizations should mitigate this circumspection.

- Changes in scientific knowledge are always changes for the better. The knowledge continues to change because it’s the new knowledge that is more reliable over the old knowledge.

- Science works. We drive our cars, “plug in” to our devices, get well by taking medicine, enhance our crop yields, etc. because the scientific principles that undergird these activities are sound, reliable.

Cognitive Resources and Personal Bias: The Double-Edged Sword

Giere (1988) has referred to cognitive resources as the knowledge we have about a particular domain and also the skills we possess to perform certain actions within that domain. A person’s cognitive resources matter because they can lead the individual, for instance, to a certain interest in a particular line of investigation that they then explore. Harry Reid had studied glaciers, how they move, their properties and behaviours, prior to studying the effects of the 1906 earthquake in San Francisco. He could make analogies, based on his past experiences with the elastic behaviour of ice, to propose elastic behaviours in the crust. Alexander du Toit and Edna Plumstead were both sympathetic to and made significant contributions to Wegener’s ideas about horizontal displacement. This was, in part, because they both grew up in South Africa, a place where evidence for drift lent credence to the idea. Further, their education also presented Wegener’s idea of horizontal displacement as a viable solution to many of the observations that were problematic for contractionism.

Think of any of the major contributors to the ideas discussed in the previous topics in this book. Would she or he have been able or inclined to make the discoveries that brought them fame, if they did not have their unique background? What if, for instance,

- Hutton had not been exposed to the mechanistic approach to phenomena, or the notions of cyclicity in the natural world from Newton’s Principia, Chapter 1.5?

- Mary Anning’s dad had not shown her about the formed stones?

- Wegener had not, among other things, had experience with drifting icebergs?

- William Smith had not been so meticulous in his fossil collecting and identification?

Without those cognitive resources, which also encompasses personal biases, we can speculate that you might not be reading about her or him today.

T H I N K Q U E S T I O N

Mott Greene, in his wonderful biography of Alfred Wegener, makes the assertion that we are not the authors of our own lives. Rather, this is the role of those around us. Newton also famously stated, “If I have seen further, it is because I have stood on the shoulders of giants.” Explain the meaning of these statements, and justify or refute them using evidence from the text or your own knowledge of history.

Understand, however, that biases based on experience do not always advance the process of science. Remember how long it took for consensus to develop for continental drift—this is a quintessential example that sheds light on the Eurocentrism of scientific understandings. This observation was not lost on the South African-based researcher du Toit, who commented that how and when Wegener’s ideas circulated and took hold would have played out much differently if geologists from non-mainstream countries were afforded the same respect as those in more dominant centres of learning.

Along similar lines, early geologists often interpreted past environments by using current environments as a proxy, a strategy that reflects a bias towards uniformity. This orientation to uniformity informed Lyell and Darwin’s perspective about the extensive age of the earth, giving them an edge over physicists and chemists, whose biases privileged the importance of natural laws and equations. However, these same ideas of uniformity acted as a partial barrier to scientific advancement, such as when the continental drift proposal emerged. To many geologists at the time, the drift explanation did not fit within a rigid definition of uniformity. Similarly, to attribute dinosaur extinction to a meteor impact was much more aligned with catastrophism than the slow and steady equilibrium proposed by uniformitarianism. These examples raise the question of when to hold onto a theoretical framework and when to jettison it for something better. There may be no easy answer, though when the data require such a move it does eventually happen. However, frequently the data are collected and viewed within the frame of a given theory, making it difficult to see an alternative interpretation or fresh implications.

Timing and the Reception of Scientific Discovery

In 1972, the molecular biologist Gunther Stent (1924–2008) published a paper in Scientific American, entitled “Prematurity and Uniqueness in Scientific Discovery.” Stent explained in the paper why some worthy scientific ideas sit around in relative obscurity, sometimes for decades, before eventually becoming the consensus view. Examples that we have covered here include the 50 or so years between Wegener’s proposal of horizontal displacement and the development of consensus around plate tectonics, and the 30-year interval between Alvarez first proposing that an impact killed of the dinosaurs and consensus on that view. Stent used examples from molecular biology as opposed to geology to demonstrate his idea, explaining that “an idea is premature if its implications cannot be connected by a series of simple logical steps to canonical or generally accepted knowledge” (2002, p. 84). At the core of Stent’s comment is the idea of “ready-ness,” that the capacity to connect the new idea to already accepted knowledge in the scientific community affects its reception. And, without a logical connection to consensus knowledge, reception is poor. In fact, an outright rejection may be the response until other factors line up to create an easier link to the new idea.

Wegener’s idea about horizontal displacement was a global answer for local observations and problems. Many geologists at the time were focused mainly on these local problems and looking only for local explanations. Wegener also had experience in geophysics, something many of his North American and European counterparts lacked. These were just two of the steps missing from the bridge that links fixism to horizontal displacement. Even in the 1950s, when paleomagnetism studies produced apparent polar wandering paths that could only be explained by drift, many geologists were not swayed. This was because paleomagnetism was a new field of study at the time, and many geologists did not understand it, let alone trust it.

In this case, the missing steps that make it is possible for the idea of horizontal movement of the lithosphere to be better received, and ultimately adopted, began to fill in when enough cumulative data emerged from various sub-disciplines of geology—seismology, geophysics, physical oceanography, paleomagnetism, volcanology, and igneous and metamorphic petrology (the study of igneous and metamorphic rocks). These steps occurred through the work of several researchers, as we have seen:

1. Wilson connected seismology with the idea of moving plates, when he predicted and then verified transform faults.

2. Morley, and Vine and Matthews put sea floor spreading together with paleomagnetism, through the idea of moving plates.

3. Robert Dietz connected (a) mantle convection from Holmes, to (b) mantle plumesnfrom Hess and Wilson, to (c) the lithosphere, to create a viable mechanism for plate motion. Very few geologists would disregard the new theory of plate tectonics after this.

4. Tanya Atwater, in her study of the San Andreas fault, showed that the theory—based mainly on phenomena under the ocean—actually made sense of observations made on the continents as well. This was the final step for verification.

References

Allchin, D. (2013). Teaching the nature of science: Perspectives & resources. SHiPS Education Press.

Boulter, C., & Buckley, B. (2000). Constructing a typology of models for science education. In J. Gilbert & C. Boulter (Eds.), developing models in science education (pp. 41–58). Kluwer Academic publishing.

Frankel, H. L. (2012). Wegener and the early debate (Vol. I). Cambridge University Press.

Giere, R. N. (1988). Explaining science: A cognitive approach. University of Chicago Press.

Gilbert, S., & Watt Ireton, S. (2003). Understanding models in earth and space science. NSTA Press.

Greene, M. T. (2015). Alfred Wegener: Science, exploration and the theory of continental drift. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Jackson, P. W. (2006). The chronologers' quest: Episodes in the search for the age of the earth. Cambridge University Press.

Stent, G. (2002). Prematurity in scientific discovery. In E. Hook (Ed.), Prematurity in scientific discovery: On resistance and neglect (pp. 22–33). University of California Press.

Thagard, P. (2012). The cognitive science of science: Explanation, discovery, and conceptual change. MIT Press.