Is Earth a machine or an agent? Finding and analyzing metaphors in geoscience textbooks

Abstract

Scientific language is replete with metaphors. A metaphor is using a known or concrete idea to stand for a less-know abstract idea. Metaphors, like any model, highlight certain aspects of a concept while hiding others. While experts are good at knowing what is highlighted and hidden, novices are much less so. Thus, students can easily develop misconceptions of new concepts.

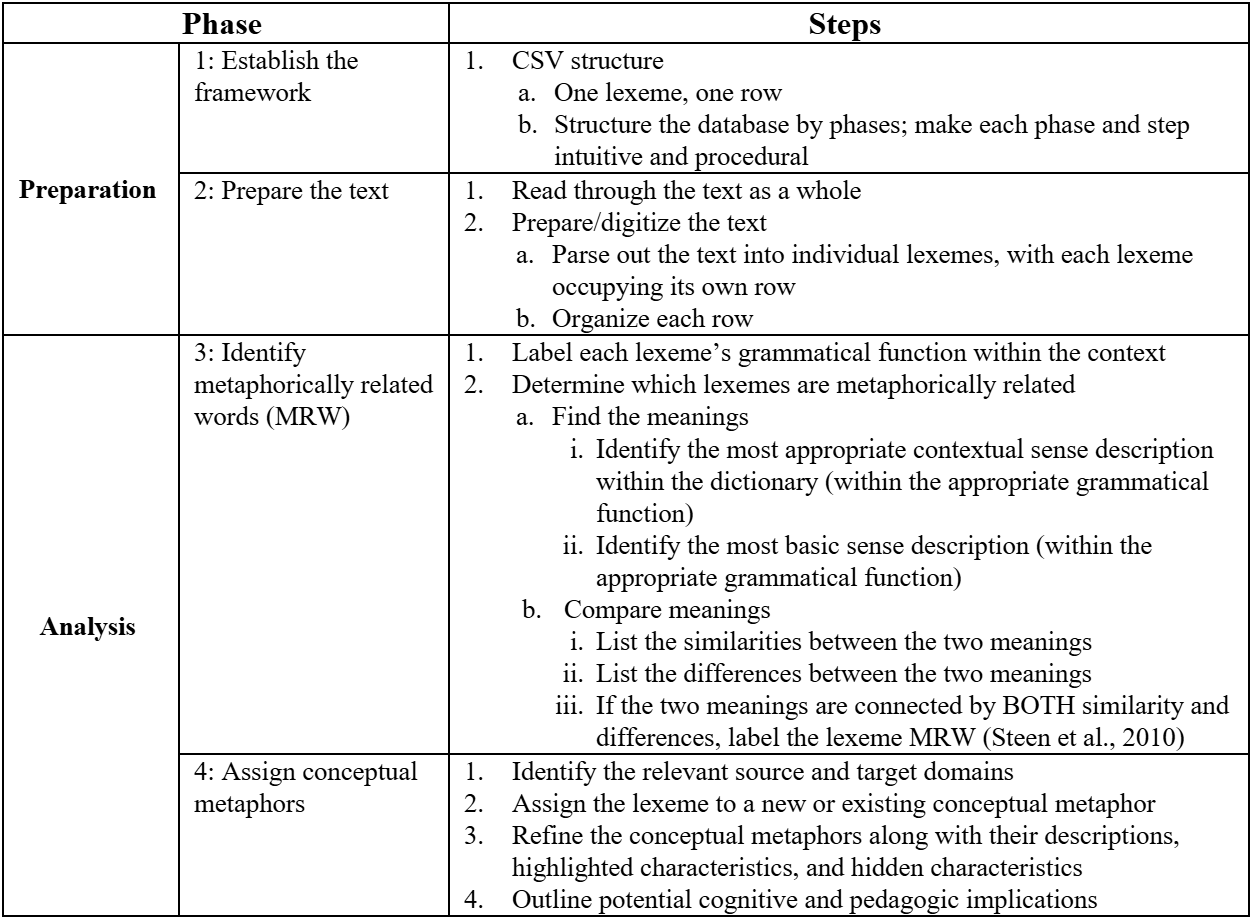

The Metaphor Identification Procedure VU University Amsterdam (MIPVU) is a common process for identifying linguistic metaphors. We have, however, simplified and streamlined this process into four main phases: 1) establishing a framework, 2) preparing the text, 3) identifying metaphorically related words, and 4) assigning conceptual metaphors.

We have also begun to identify and analyze the metaphorically related words present in introductory undergraduate geoscience textbooks; the hope here is to establish a baseline inventory of the common conceptual metaphors characterizing geoscience education, along with the potential pedagogic consequences.

Given the inherent complexity of metaphor analysis, we encourage science educators to “follow the spirit, not the rules” of MIPVU and other metaphor analysis procedures. This involves acknowledging the prevalence of metaphors in language and their fundamental role in thought and learning. It also involves thinking carefully about the source domains, as well as the most salient characteristics students are likely to pull from and project when formulating new concepts. In this way, educators may enhance their educational techniques to realize the desired learning outcomes.

Introduction

According to constructivist learning philosophy, humans learn by incorporating concrete experiences of the real world––either through accommodation or assimilation (Indurkhya, 1992)––with their previous knowledge (Driscoll, 2005; Posner et al., 1982) in a bootstrapping manner (Carey, 2009). Comprehension starts in the mesocosm––the scale of everyday human experience––whereby learners develop meaning of concrete objects or phenomena through embodied experiences with them (Clark, 2011; Niebert & Gropengiesser, 2015; Shapiro, 2011). A child learns that things fall to the ground by dropping them, that dog fur is soft by petting the animal, and that candy is delicious by tasting it. Abstract concepts so common in geoscience, however, present significant challenges to learning because they exist at scales of time or space well outside of everyday human experience; further, they reference events that happened in the past, or are otherwise inaccessible, such as those that happen below the earth’s surface. This being the case, there needs to be a bridge from the concrete to the abstract. Metaphors commonly fill that role.

A metaphor usese a familiar concept––the source concept––to stand for or give meaning to a less well-known concept––target concept––in a process called mapping. Through mapping, aspects of the source concept are matched with parallel aspects of the target concept. Metaphors, then, both highlight and hide certain aspects of a target concept (Entman, 1993; Lakoff & Johnson, 1980, 1999). Take, for instance, the metaphor “black hole” and each of its constituent lexemes.1 Holes, in general, are voids, an absence of matter and light. They are often in shadow, can be filled with matter, and are generally circular. These characteristics are, in fact, highlighted in the black hole metaphor. However, this metaphorical framing does not highlight, and thus hides, many other important black hole characteristics.

A black hole is not absent of matter; quite the opposite in fact. It is an extremely dense ball of matter, a key characteristic hidden by the metaphor. The metaphor may even be contributing, for example, to the common conception that a person can enter a black hole to travel to another dimension or part of the universe. This is akin to Michael Jordan traveling through a golf hole to another universe in the film Space Jam. Importantly, because experts think differently about their domain of study than novices (Clement, 2008), they are much better at navigating such nuances. Metaphors, however, could undermine learning for novices if they are unable to distinguish the salient aspects of the metaphor from its incidental limitations (Dolphin & Benoit, 2016).

Lakoff and Johnson (1980) showed that metaphors are not simply relegated to the function of superficial adornments in poetic writing, but instead structure much of our language, thought, and learning. Scientific terminology is replete with metaphor—for example, greenhouse effect, DNA code, big bang, elastic waves, space-time fabric, elementary particles or strings, and laws of nature. Therefore, understanding which metaphors get used in science education, both in the language of science and the language of science education is an important piece of pedagogical content knowledge (Amin, 2020; Petrie & Oshlag, 1993). It is with this aim that we have embarked on this pilot study. We investigate the following questions:

RQ1: What metaphors can we identify in an introductory geology textbook that would influence how students learn within that domain?

RQ2: How might students understand geoscience concepts in light of the use of these metaphors?

To answer these questions, we have chosen to rely upon Conceptual Metaphor Theory (Lakoff & Johnson, 19880) for our theoretical foundations and the Metaphor Identification Procedure VU University Amsterdam (Steen et al., 2010) for linguistic metaphor identification.

Theory

The philosophical foundations of this work rest on constructivism. Within this tradition, learners are not conceptualized as merely empty vessels waiting to be filled or blank slates to be written upon with knowledge, but as participants active in their environment, constructing understandings by creating, moderating, testing, and amending personal models of that environment (Driscoll, 2005). The learner creates schemas (Rohrer, 2005; Rumelhart, 1980), as mental representations or mental models (Núñez-Oviedo et al., 2008) of reality. In other words, they create object concepts, and operators to represent the reality of objects and transformations, respectively (Indurkhya, 1992). They then test their mental model against reality (Clement, 2008) and if dissatisfied with the original model’s results, tend to adjust the model to better fit their observations; this process is identified as “accommodation” (Posner et al., 1982; Strike & Posner, 1992). While learners sense the information from the environment, they also unconsciously project meaning onto it (Indurkhya, 1992), which influences how they perceive the information. This explains how learners make meaning for concrete objects or processes, grounded in embodied experience (Pecher et al., 2011). However, there are many abstract ideas, such as “love” or “understanding,” as well as most scientific theories like, elastic rebound, plate tectonics, or natural selection, etc. We have used metaphor to reason about the phenomena and to help teach it, bridging the gap between abstract concepts and concrete experiences.

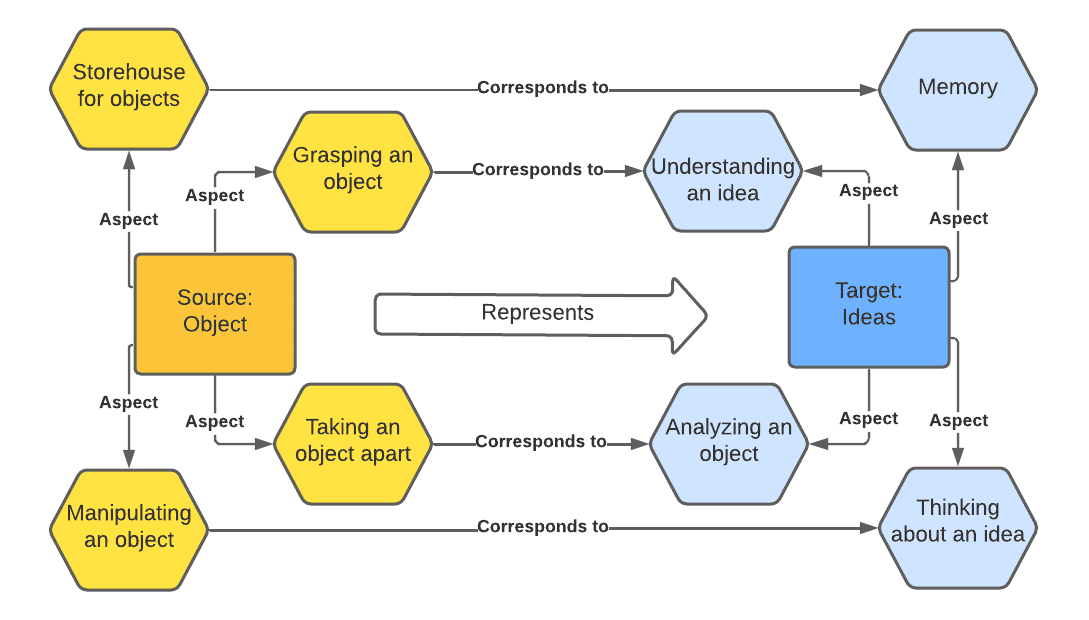

Scholars began paying serious attention to the use of metaphor and its impact on thinking and reasoning about concepts in the late 1970s (Lakoff, 1993; Lakoff & Johnson, 1980, 1999; Reddy, 1979). Their ideas were organized into the highly influential Conceptual Metaphor Theory (CMT). CMT is a psycholinguistic theory, one which posits that both natural language and general cognition are metaphorically structured as neural mappings in the brain (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980). Language both structures and is structured by metaphor at a neural level. There are, thus, two different types of metaphors: linguistic and conceptual.2 Linguistic metaphors are the material traces and triggers of conceptual metaphors, which are themselves the neurological mappings in the brain that pull from a source domain in the brain (that is, the synaptic structure) to construct a new target domain (Figure 1).

By uncovering and describing metaphor usage in natural language, researchers and educators can both anticipate the likely meanings made by learners of the target concepts, as well as the cognitive schemas and associated neural structures already in use. Experiences with the source automatically and unconsciously frame how one considers the target (Kahneman, 2011; Lakoff & Johnson, 1999). For instance, Thibodeau and Boroditsky (2013) showed that people reading about crime through the metaphor of CRIME IS A BEAST ATTACKING or CRIME IS A VIRUS INFECTING preferred different approaches for addressing crime–enforcement versus reform, respectively. Dolphin and Benoit (2016) also showed that university students had difficulty understanding elastic rebound theory when learning about the mechanism of earthquakes because the metaphor, the LITHOSPHERE IS A PLATE, framed their understanding of lithospheric plates as dinner plates; separate and brittle. Others have advocated the direct—that is, strategic and intentional—use of metaphor in science education (Amin, 2020; Berger, 2016; Brown, 2020; Niebert & Gropengiesser, 2015).

Metaphors can inform a student’s understanding of scientific concepts; thus, we wanted to take a systematic look at the metaphors that are invoked within a geoscience text. Since linguistic metaphors are taken as traces of conceptual metaphors, conceptual metaphors and their characteristics can be inferred from their associated linguistic counterparts. In particular, we are interested in documenting two uses of metaphors, those used in the scientific names of concepts, tectonic plate, layer cake stratigraphy, seismic waves, and so forth, and also common metaphors used incidentally within the text and reflecting how the author thinks about the topic. Once we have delineated some of the common metaphors in the texts, we plan to analyze those metaphors for what they highlight and what they hide about reality. It is especially important to understand what the common metaphors hide about the target concept, since this may be a source of common misconceptions (Cheek, 2010; Francek, 2013).

Methodology

MIPVU

The Metaphor Identification Procedure VU University Amsterdam, or MIPVU, is a method for identifying linguistic metaphor (Steen et al., 2010). It is an expanded and refined method based on the original Metaphor Identification Procedure (MIP) by the Pragglejaz Group (2007). Because of its systematic approach to identifying metaphor in discourse, it is a largely transparent procedure, maintaining high inter-coder reliability (Steen et al., 2010).

The practitioner begins the procedure by reading the text to generate a basic understanding of what it is about. Then the reader identifies the lexemes, which are usually based on a single word. The reader then reflects the contextual meaning of each lexeme at a time and uses a standard lexical corpus (like a dictionary) to identify a more basic definition, if one exists. “More basic” means more concrete or body-related. This is often the earliest meaning but does not have to be the most common or frequently used meaning. If the contextual meaning is defined differently from the most basic or concrete meaning (usually designated by a different definition number), then the word is considered a metaphor.

Our Adapted Process

We actualized the MIPVU rules and the CMT assumptions into a phased and stepped system for identifying, describing, and understanding linguistic and conceptual metaphors in use. The process is structured around four sequential phases.

Preparation

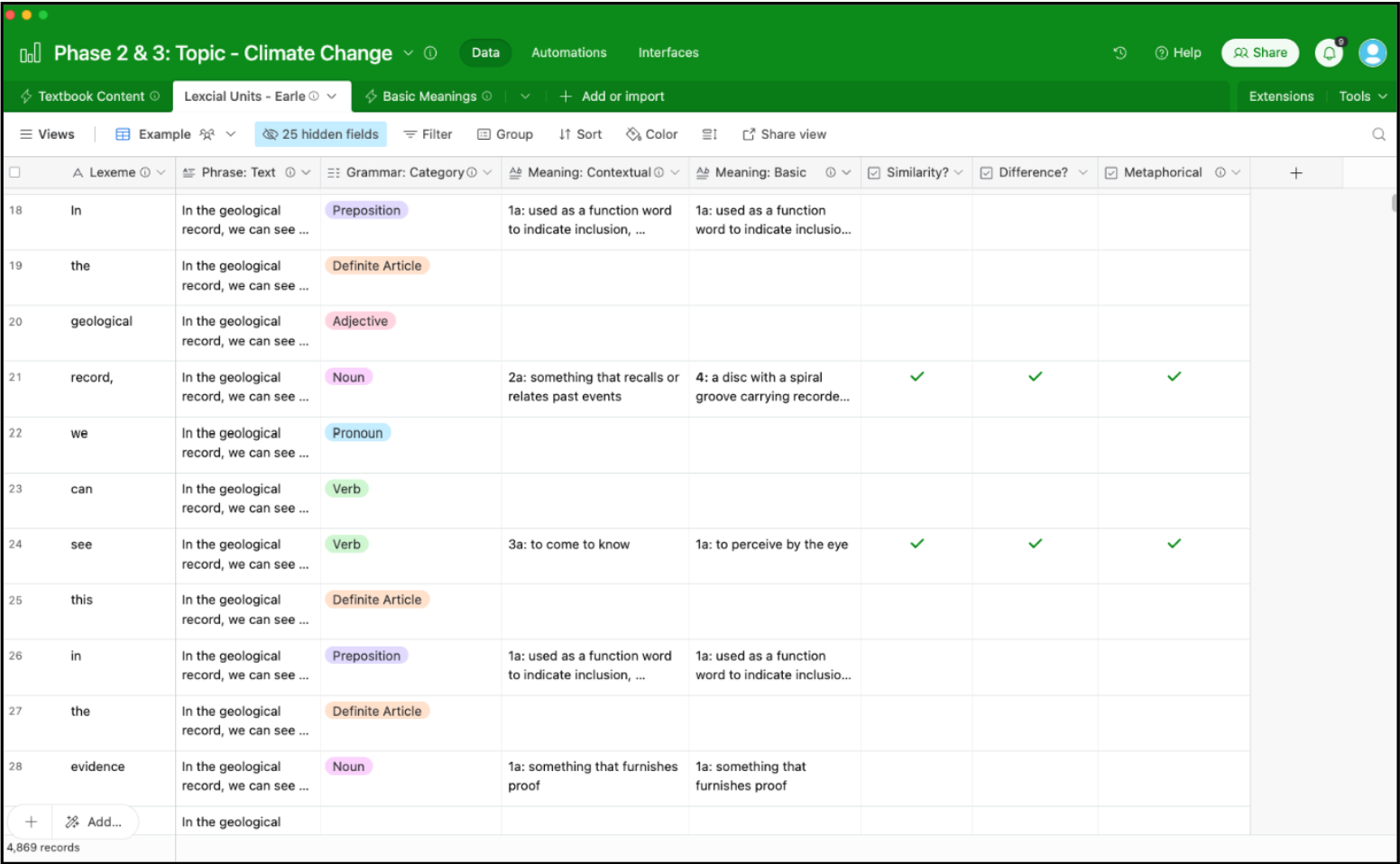

Our process first requires that we establish a robust and intuitive framework that facilitates data collection, organization, and analysis. Since MIPVU operates at the level of the lexeme, whole texts must be parsed into individual lexemes, and analytic software must enable detailed descriptions of each. We found comma-separated value (CSV) formats, rather than markup, was best suited to these demands (see Figure 2).3

Next, researchers would prepare the text by reading fully through it and migrating it into the analytic framework. Since MIPVU directs analytic attention to individual lexemes, one at a time, lexical collocates, phrases, images, whole texts, and the relevant context run the risk of being ignored. To remedy this, analysts would read through and gain an intimate understanding of the whole text before focusing on lexemes. In fact, researchers would reflexively adjust their focus throughout the whole analytic process, focusing on lexemes for a time, then zooming out to the whole text or context, then back to the lexemes, and so on. The text can then be prepared by parsing it into individual lexemes—allocating each into its own row—and applying the appropriate codes to ensure that everything remains organized.4

Analysis

Once the first two phases are complete, analysis of the text and its metaphoricity may begin. This can be broken down into multiple steps. First, researchers label each lexeme’s grammatical function within the context. For example, the lexeme “record” in the phrase “the layers of rocks record Earth’s geologic past” would be labeled as a verb, but a noun in “the geologic record helps us understand Earth’s geologic past.” This distinction is important because, according to MIPVU, linguistic metaphors only operate within their respective grammatical categories. While we believe this assertion is not without issue, we recommend treating this as the default principle

Next, researchers must determine which lexemes are metaphorically related words (MRW) by comparing the contextual and basic meanings. This begins with identifying both the contextual and most basic meanings, or sense descriptions, based on a single dictionary. For example, in the phrase “the geologic record helps us understand Earth’s geologic past” the contextual meaning might be Merriam-Webster’s sense description 2a: “something that records: such as something that recalls or relates past events” (Merriam-Webster, n.d.-b). In contrast, the most basic meaning might be sense description 4: “something on which sound or visual images have been recorded” (Merriam-Webster, n.d.-b).

The contextual and basic meanings are then compared, to see if they are simultaneously different but connected by similarity. Continuing with the previous example, the contextual and basic meanings are different since they are associated with different sense descriptions (2a and 4). They are also connected by some similarity in that they share similar qualities; they both connote some sort of durable accumulation of information that can be referred to and interpreted. This use of the lexeme “record,” then, would be labeled as MRW.

In the final phase, researchers use MRWs to infer the possible corresponding conceptual metaphors, their relevant domains, the characteristics they are most likely to highlight and hide, and their potential cognitive and pedagogic consequences. Here, the MRW “record” could be associated with a conceptual metaphor that pulls from the source domain (or concept) of VINYL RECORD to help the reader construct the concept of GEOLOGIC RECORD. Hence, this yields the metaphor THE GEOLOGIC RECORD IS A VINYL RECORD. Vinyl records have a host of characteristics: information, especially that which is a trace of some aspect of reality; something that is preserved and readable; and something with flatness, brittleness, circularity, and other physical qualities. If students do indeed pull from the concept of VINYL RECORDS to construct the concept of GEOLOGIC RECORD, these are the likely characteristics involved. Educators, then, should think carefully about which of these characteristics they are comfortable with being projected onto the concept of GEOLOGIC RECORD—and those they are not.

Table 1: Modified MIPVU Metaphor Identification Process

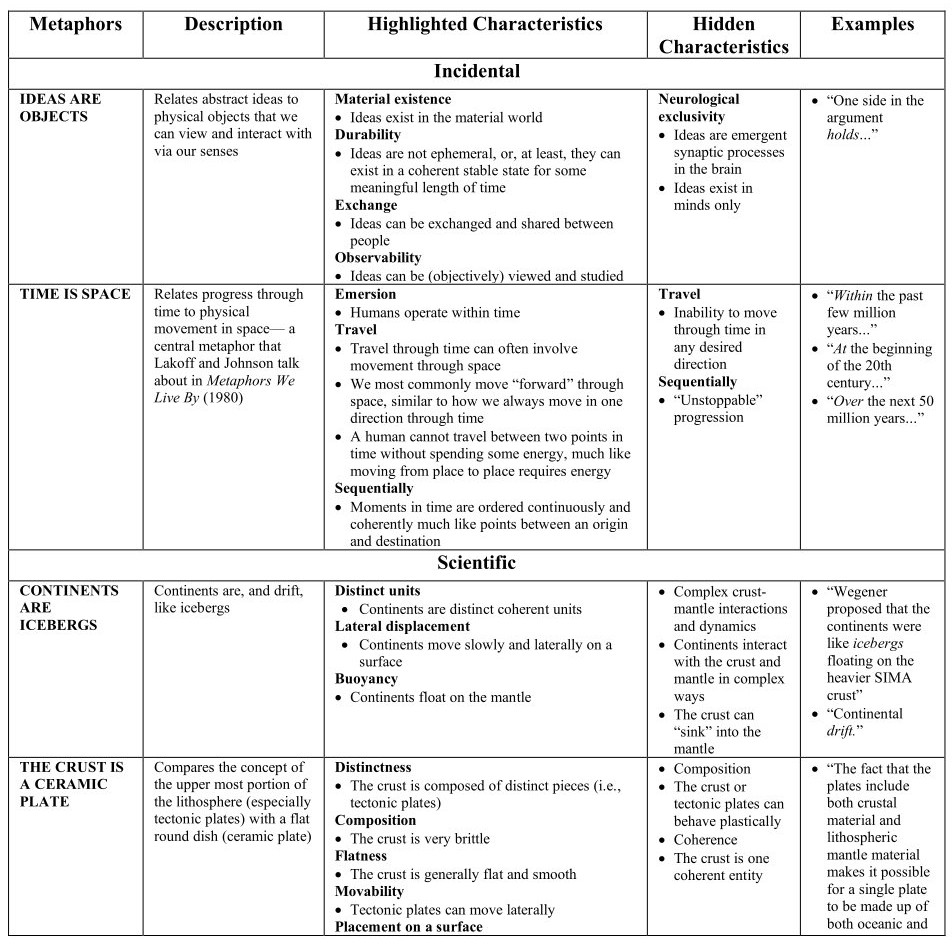

Preliminary Findings

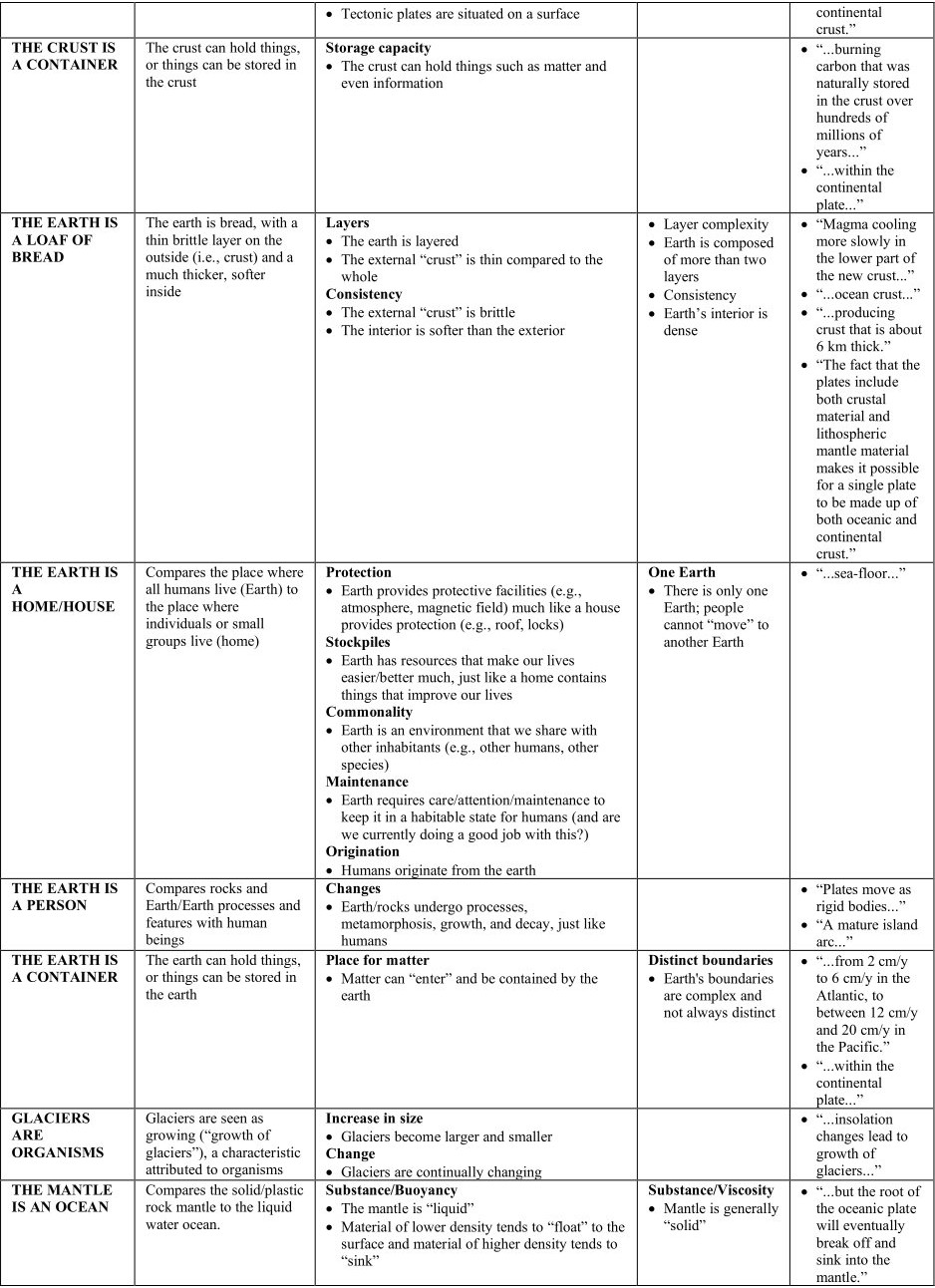

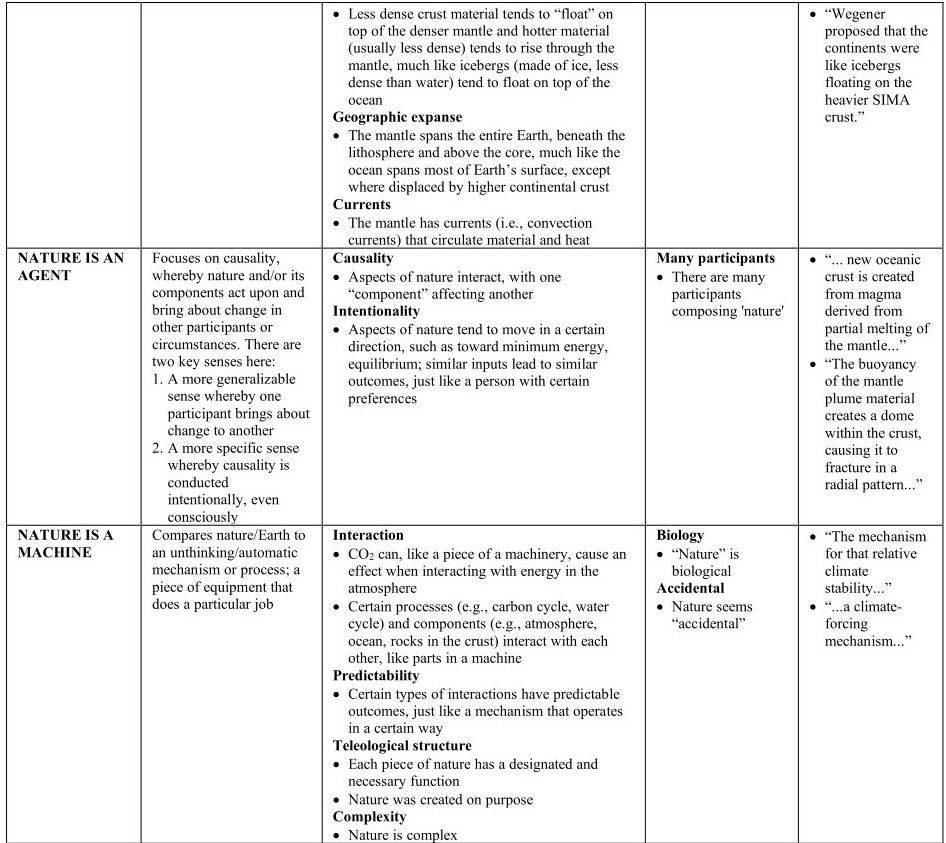

To answer our first research question— What metaphors can we identify in an introductory geology textbook that would influence how students learn within that domain?—we have thus far analyzed two chapters of Steven Earle’s (2019) Physical Geology open educational resource textbook: chapter 10 (Plate Tectonics), and chapter 19 (Climate Change). We have identified numerous metaphors, some of which are included in Table 2; we found that, for our purposes, most of them can generally be divided into incidental and scientific concepts. General concepts are those such as “concepts,” “time,” “space,” and “experience.” Scientific concepts are those related to “nature,” “Earth,” “rocks,” “the mantle,” and the like.

Table 2: Conceptual Metaphors and Their Characteristics

Incidental Metaphors

Two especially salient and pervasive metaphors that we identified as incidental use are IDEAS ARE OBJECTS and TIME IS SPACE.

Ideas Are Objects

The metaphor IDEAS ARE OBJECTS occurred 49 times in the two chapters analyzed. It relates abstract ideas to physical objects that we can view and interact with via our senses. For example, consider the description that an idea is “built” and/or “stored” in our brains, much like a physical object can be constructed or put inside a container. An idea such as an “argument” can “hold” an idea, construed as an object:

- “One side in the argument holds that the plates are only moved by the traction caused by mantle convection.”

In trying to develop an explanation for plate motion in the above example, the author suggests, based on metaphor use, that the explanation, “traction caused by mantle convection,” is an object that can be held. This use of metaphor is very common in all communication (Grady 1999; Reddy, 1979), where we speak of communication as the transfer of ideas, just as we would speak of the transfer of objects from one person to the other. Consider the following sentences:

- “The professor delivered the lecture to an eager classroom.”

- “The student had an open mind and was receptive to what the professor was saying.”

Such expressions of communication are common and reflect our perception of transferring knowledge during communication, where someone says something, and we learn it. However, consider what happens during communication. One either reads a communication or hears it. In the case of reading, the reader is not receiving knowledge from the text, but only observing black symbols on a white page. The symbols have meaning to the reader only if the reader is familiar with the language. The symbols do not have any intrinsic meaning. If this were the case, then one would not have to know English to read and understand something written in English. Moreover, making meaning of the symbols is done in the mind of the reader.

The same is true for hearing. A lecturer does not transmit knowledge with their voice. They merely create vibrations in the air, alternating compressions and expansions of the air. These compressions and expansions travel through the air and eventually vibrate the listener’s ear drums causing them to move the bones in the inner ear, which eventually trigger nerves that send the message of vibrations to the mind. It is the listener’s mind that decodes the signals and gives them meaning. We are unaware of the knowledge construction that is happening within our mind; therefore, we perceive learning as us physically receiving knowledge from the book or lecturer. Because we have a great deal of experience giving and receiving objects, our minds use that experience to explain and give meaning to the process of communication.

Another example from the text that supports the metaphor CONCEPTS ARE OBJECTS indicates that how we understand an idea is related directly to how we see it:

- “Another widely held view was permanentism, in which it was believed that the continents and oceans have always been generally as they are today.”

This example showcases multiple examples of the metaphor. Permanentism, a 19th century explanation for the existence of mountains and ocean basins, is a mental construct. In the sentence above, it is something that we can see, a view. Of course, we cannot actually see this idea, but the metaphor concretizes it as an object in our line of sight. Not only is this object something that is manipulable, something that can be held, but it is also a container in which beliefs (other objects) are found or stored.

Time Is Space

Throughout the analyzed parts of the textbook, one central metaphor we observed is TIME IS SPACE, which relates advancement through time to physical movement in space (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980; Moore, 2014). This metaphor links the concepts of time and space, by representing aspects of time with aspects of space (Moore, 2014).

We see this metaphor in common communications such as the following:

- “Winter is drawing near, in fact, it’s just around the corner.”

- “The weeks ahead are going to be very busy with classes.”

- “I finally made it to summer and warm weather.”

- “The days following my stay at the hospital were quite restful.”

In the above cases, a path is a metaphor for the passage of time; either events are moving with respect to the person in the sentence (winter drawing near, days following), or the person is moving (I made it to summer) with respect to events along the path (weeks ahead). This metaphor is very common because time is such an abstract concept, yet we often need to talk about it and our relationship to it. Similar to our vast experience with manipulating objects, as described above, we have a great deal of experience traveling along paths or roads, or taking a journey, making the concept easy to understand and reason about.

This metaphor is particularly important in geology because time—a very abstract concept—is a fundamental aspect of geological understanding (Cheek, 2012; Dodick & Orion, 2006; Rudwick, 2005). Geologists are constantly substituting space for time. Nicholas Steno’s principle of superposition has the implication that the deeper one digs into sedimentary rock layers the further back in time one would go. Annual varves (layers) of clay and silt are assigned one year of time each. In fact, any change in rocks from their original formation (such as through metamorphosis, folding, faulting, and similar processes), would represent some passage of time. Before the development of radiometric dating, many geologists calculated the age of the earth using the total thickness of sedimentary rocks, divided by an average sedimentation rate (Jackson, 2006). Unconformities, designated as a gap between two layers either from lack of deposition or because layers eroded prior to deposition on top, represent zones where time is “missing;” either it was never recorded, or erosion erased it.

Examples from the data that use the metaphor of TIME IS SPACE are as follows.

- “Between 200 and 150 Ma, rifting started between South America and Africa and between North America and Europe, and India moved north toward Asia.”

- “This situation [the opening of the Atlantic Ocean] may not continue for too much longer, however.”

- “Over the next 50 million years, it is likely that there will be full development of the east African rift and creation of new ocean floor.”

In the above examples, the author makes use of the TIME IS SPACE metaphor when describing the timing of different phenomena taking place on the earth. In all cases, a line that references time, along with positions along that line, represents the phenomena (rifting, in the examples above).

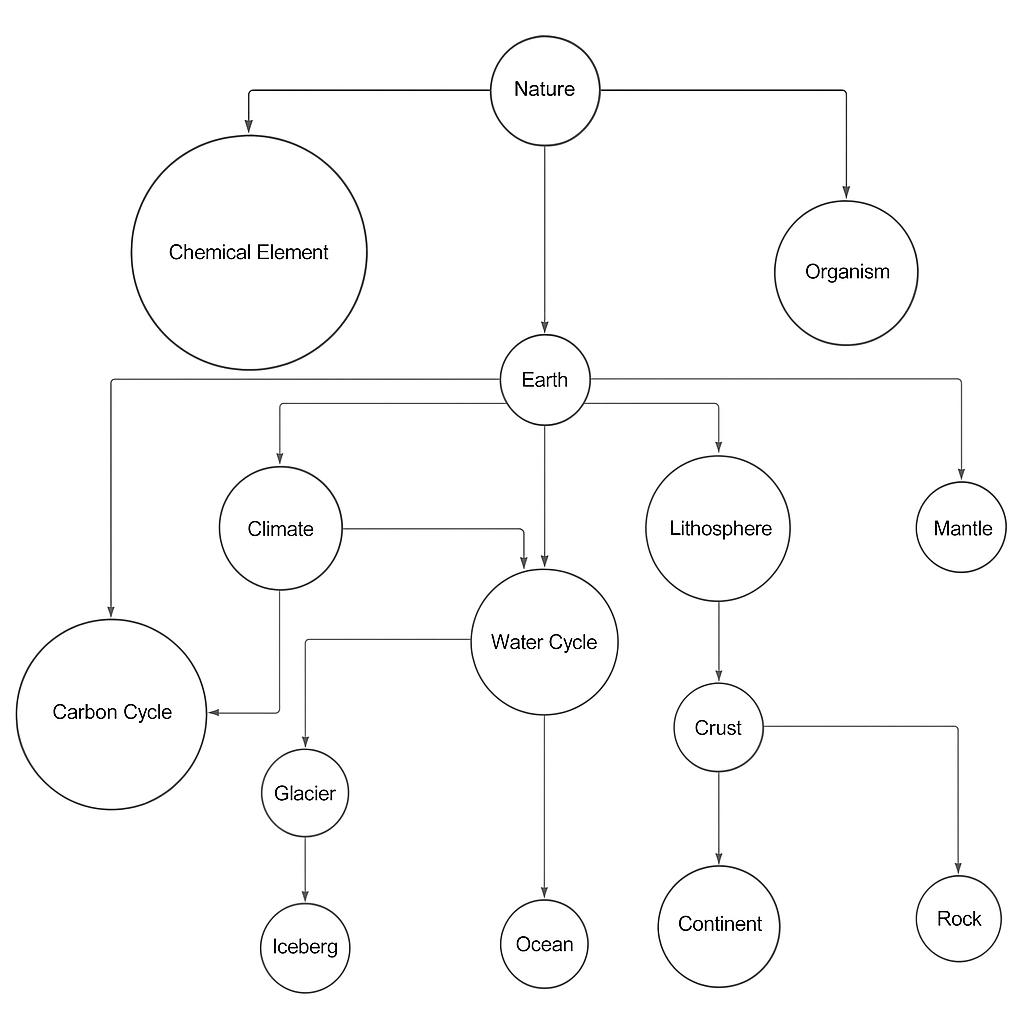

Scientific Metaphors

The scientific concepts of particular interest for this study are, unsurprisingly, relate to the earth (Figure 3). Common concepts present in the dataset, such as “mantle,” “lithosphere,” “climate,” and more, were all grouped under “Earth.” The earth itself, however, was taken as a subset of the concept of “nature.” Thus, the broadest metaphors are those relating to nature. Two are particularly omnipresent in the data: NATURE IS A MACHINE and NATURE IS AN AGENT.

Nature Is a Machine

The metaphor NATURE IS A MACHINE is quite old, becoming more popular as technologies began to develop during the 16th and 17th centuries. Historians place the origin of a closely related metaphor, LIFE IS A MACHINE, with Descartes, which was his reaction to his experience with lifelike hydraulic automata prevalent in the gardens of royalty and the wealthy (Marques & Brito, 2014). Additionally, the Enlightenment, continued industrialization, and especially Newton’s application of metaphor to the universe via his characterization of it behaving like clockwork continued to reinforce and popularize the metaphor.

Later, in the early 18th century, James Hutton described the dynamics of the earth, how continents rose from the seas and how mountains rose above continents, due to the earth’s internal heat engine (Norwick, 2002), which further amplified this machine metaphor. In his book about the history of climate science, A Vast Machine, Edwards (2013) likens the earth’s atmosphere to a machine, through the 19th century words of John Ruskin. The transition toward this metaphor arose from the shift from teleologic causation (see NATURE IS AN AGENT below)—eventually deemed unscientific—to a more efficient and objective causation (Marques & Brito, 2014). Passages from the text that use this metaphor follow.

- “Wegener could not conceive of a credible mechanism for moving the continents around.”

- “That makes CO2 solubility another positive feedback mechanism.”

- “The mechanism for that relative climate stability has been the evolution of our atmosphere.”

- “…other parts of the thermohaline circulation system.”

In the above quotes, the author of the textbook refers to aspects of the earth—in this case, plate tectonics and climate—as mechanisms, part of a larger machine whose role it is to move continents or set climate, respectively.

This metaphor seems to highlight characteristics that most relate to functionality, complexity, interaction, and predictability. Specifically, nature is a complex, functional system composed of many interacting components, each with its own function and purpose, which all interact (ideally) in a predictable manner to produce some sort of product, process, or outcome. Yet, this metaphor also hides a host of potential natural characteristics, such as Earth’s biological processes and its potential accidental and purposeless existence.

Nature Is an Agent

The metaphor NATURE IS AN AGENT focuses on causality, whereby nature and/or its components act upon and bring about change in other participants or circumstances. This is a common metaphor in scientific discourse given the particular concern with processes, causality, and effects. Two distinct senses of agency are evident here, one weaker and one stronger. The weaker sense denotes causal change whereby one participant brings about change to another. Here, nature or a part of nature effects change in another part, or arrangement, of nature. The verb “causing” in the following excerpt demonstrates this:

- “The buoyancy of the mantle plume material creates a dome within the crust, causing it to fracture in a radial pattern.”

A dome (the agent) causes the crust to fracture (the effect). News media often frame nature in this way, with such headlines as, “Florida beachfront paradise shattered by Hurricane Ian5,” “Nepal earthquake kills at least six villagers, rattles New Delhi6,” or “Wildfire smoke chokes U.S. Northwest: Residents don masks7.” In all these cases a natural phenomenon is acting on or even against humans and their society (shattering, killing, rattling, or choking).

The stronger sense of agency, however, denotes causality that is conducted intentionally, even perhaps consciously. This sense may also be present in the previous example via the verb “creates.” Most example phrases under the entry for “create” in the Merriam-Webster online dictionary, for instance, entail human or human-like agents (Merriam-Webster, n.d.-a). We are of the mind that most people interpret the lexeme “create,” in this and most circumstances, as anthropomorphic, intentional, and volitional to some degree. In public discourses, for example, nature is often imbued with emotional characteristics. The earth, or nature, are often described as “angry” during the more extreme storms, earthquakes, or natural disasters.

Entailments

The principle of “entailment” suggests that characteristics of one concept project onto its relevant parent (superordinate) and/or daughter (subordinate) (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980). Entailments emerge from a conceptual metaphor. This means that for the superordinate metaphor IDEAS ARE OBJECTS, one could expect the presence of subordinate metaphors, or entailments, such as THINKING IS MANIPULATING OBJECTS, MEMORY IS A STOREHOUSE/CONTAINER, UNDERSTANDING IS GRASPING, COMMUNICATING IS SENDING, and ANALYZING IDEAS IS TAKING APART OBJECTS. If NATURE IS A MACHINE (superordinate), we can expect entailed metaphors (subordinate) like EARTH IS A MACHINE along with others down the hierarchy. Two such examples from our dataset are THE CARBON CYCLE IS A MECHANISM and THE WATER CYCLE IS A MECHANISM.

We have also found that some metaphors do not cohere across many hierarchies, standing alone to perform specific functions. For example, THE EARTH IS A LOAF OF BREAD, is generally relegated to the MRW “(Earth’s) crust” but few, if any, other metaphors. Along with its two potential subordinates, EARTH’S CRUST IS A BREAD CRUST or EARTH’S MANTLE IS BREAD, this metaphor specifically highlights Earth’s layers, the crust’s thinness in particular, and the variant consistency of such layers—namely, the crust’s brittleness and the mantle’s relative plasticity.

Other metaphors integrate interordinates well, without necessarily having a cohering superordinate. For example, THE MANTLE IS AN OCEAN and CONTINENTS ARE ICEBERGS do not seem to share a relevant superordinate metaphor. Continents are like icebergs in that they are distinctly buoyant, yet massive, units that float and slowly travel laterally. They “float” on the mantle and are moved by it, in part, due to currents (that is, convection currents). These two metaphors interact to facilitate the concept of continental drift.

Of course, continents are not icebergs, and the mantle is not an ocean. Thus, while these and other metaphors help facilitate learning and cognition, they also likely contribute to undesirable learning outcomes.

Discussion

The reader might be asking what benefits lie in performing such analysis of a text, or even lectures. We claim that several short- and long-term benefits arise from this practice. Such short-term benefits could be in anticipating times when students are likely to develop understandings of concepts that diverge from what the instructor intended. It can also guide an instructor about choosing appropriate metaphors for teaching. With respect to long-term benefits, science texts often demonstrate an objectivist epistemology (such as NATURE IS A MACHINE and CONCEPTS ARE OBJECTS) that has implications for understanding the nature of science and the scientific process. A metaphor analysis also contributes to how we understand teaching and learning. As well, learning to be critical of metaphors can help students better understand concepts and become more reflective about their understanding.

Short-term Benefits

Metaphor use in science is extremely common. Though often thought of as an adornment, metaphor use is important in science and, indeed, has been used often to initiate new developments (Gruber & Barrett, 1974; Nersessian, 1985, 2002). Nonetheless, because the source concept of a metaphor cannot represent the target concept in its entirety, the metaphor also hides aspects of the target. For experts on that concept, this is not a problem. They know what is highlighted and hidden. For novices to the concept, however, it is not that easy. As brought up earlier, Dolphin and Benoit (2016) demonstrated how the metaphor LITHOSPHERE IS A PLATE caused difficulty for students developing an understanding of the mechanism of earthquakes.

Of course, we are not about to change the language of science, but we can preempt the difficulty by supplying a different metaphor—such as THE LITHOSPHERE IS THE SKIN OF THE EARTH—to give students a better conceptualization of the lithosphere. In this case, that would be the elastic properties and wholeness of the lithosphere, prior to introducing the plate metaphor. For a metaphor to be effective, the students must have some experience in the source domain (Niebert & Gropengiesser, 2015; Niebert et al., 2012). In the previous case, all students have experience with their own skin. The instructor could also lead some demonstrations or provide students with experiences to subsequently leverage their meaning making, ideally maximizing the probability that students use those experiences when developing their understanding of the target concept. This is especially helpful when considering students from different cultures, whose experiences are different or where the meaning of experiences might be different. Using multiple metaphors (models) for the same concept also has the advantage of helping students develop a more robust conceptual understanding (Boulter & Buckley, 2000; Gilbert et al., 2000).

Long-term Benefits

The long-term benefits start to become obvious when investigating the epistemological implications of some of the more general and common metaphors. For instance, NATURE IS A MACHINE is highly reductive, causing us to simplify nature into component parts. As we can take machines apart and study individual components (parts with individual functions) and how they “fit” into the larger whole, so can we take bits of nature and study them as parts of the larger aspect of nature (Marques & Brito, 2014). Rout and Reid (2020, p.947) outlined four assumptions that arise from this metaphor:

- All of nature behaves like a machine.

- Just as machines are predictable (controllable), if we figure out the mechanisms in nature, we can predict and control nature (deterministic as opposed to stochastic).

- Only humans have a mind and therefore we are the only ones with intrinsic worth.

- Humanity can and should control (operate, have dominion over) nature.

Rout and Reid (2020) go on to assert that the mentality emphasized by the metaphor does more:

[Metaphor] has also had an enduring impact on economics and politics, with the axiomatic principles that emerge from these assumptions—the primacy of rationality over emotion, the centrality of the individual over the collective, the drive for progress rather than balance, and the importance of universality over locality—helping to empower capitalism and its colonializing impetus... turning nature into a commodifiable machine for human use. (p. 948)

Importantly, the metaphor causes us to see ourselves as external to the machine, as though we might be technicians or operators. It thus hides the fact that we are a part of nature. The metaphor also implies that effects are (or at least should be) completely predictable. If we know all of the parts of the machine and what each part does, the outcome of the machine working is something we can know. This implication completely hides the nature of chaos and how little tweaks in a complex system could lead to unpredictable results (Gardini et al., 2020). Critically reflecting on these assumptions can help diminish these more destructive ideologies.

More generally, the metaphor IDEAS ARE OBJECTS carries implications that affect how we think about science knowledge, since invoking this metaphor, students could develop the idea that science knowledge is ready-made and just waiting to be discovered. The metaphor completely hides—disregards even—the constructivist nature of scientific knowledge development; it also hides the role of scientist bias in scientific advances, and the influences of social, political, and economic factors on the process of science. Whether that concept is a field where scientists blaze a trail, push the boundaries, or dig for answers, or the concept is an object you can hold in your hand, a piece to a larger puzzle, something we can uncover, discover and grasp, the implications of these metaphors completely disregard the constructed nature of scientific knowledge.

Dolphin (2024) researching how undergraduate students understood science process, science knowledge, and scientist, showed that the student participants described which implied the metaphor SCIENTISTS ARE TECHNICIANS. Student participants responding to a prompt wrote that they knew they were doing science because they had on a lab coat and goggles, were working with microscopes, or titration equipment, mixing chemicals, doing dissections, following directions, writing up lab notes, and so forth. These are certainly part of the scientific process, but they are all things a technician would do. None of the student participants mentioned activities like solving problems, answering questions, making predictions, creating explanations, i.e., all the cognitive aspects of the scientific endeavor. SCIENTISTS ARE TECHNICIANS is an entailment of SCIENCE KNOWLEDGE IS AN OBJECT because according to this metaphor, there is no construction of science knowledge necessary. It is already predetermined and just needing to be discovered, uncovered, dug up, and brought to the surface. It also is an entailment for NATURE IS A MACHINE. Again, the idea of construction of knowledge is hidden. If a machine is “broken,” then we call a mechanic, a technician to fix it. The metaphor highlights this aspect of the role of a scientist, to “tinker about” using a trial-and-error approach and adjust the appropriate cog, switch, or spring to get everything running smoothly, predictably again. The notion of attributing trial-and-error to scientific methodology is a common error by conflating science with engineering and technology (Jadrich & Bruxvoort, 2013; Rau & Antink-Meyer, 2020)

SCIENCE KNOWLEDGE IS AN OBJECT also has implications for teaching and learning. If ideas are indeed mere objects to be transferred from instructor to student, then teaching, most efficiently, is handing over that knowledge, delivering it to students. For students, learning is nothing more than being receptive, having an open mind and cramming it in, only to regurgitate knowledge tidbits for the final exam. This metaphor highlights a transactional nature of teaching and learning while obscuring all the work involved in gathering information from the environment and assigning meaning to those stimuli, along with developing an understanding based on that. Critical analysis of such metaphors could help students be more active in their learning and encourage instructors to be more thoughtful about instruction.

Methodological Challenges

Many of the difficulties with the MIPVU method emerge from its fundamental level of analysis, the lexeme. The choice to focus on the lexeme attempts to capture “the functional relation between words, concepts and referents in discourse analysis” (Steen et al. 2010, p. 39). But, such a microscopic resolution leads to an arduous, data-heavy analysis that also blurs the surrounding collocations and textual landscape.

Four issues caused the most difficulty for the researchers: analytic time and capacity, textual blindness, delineating the lexeme, and determining the “most basic” meaning. Looking up the basic and contextual meanings in the dictionary, making a metaphorical judgment, and further analyzing every single word in a 10,000-word text is arduous to say the least. MIPVU analysis produces significant amounts of metadata for each lexeme, which also makes it difficult to find sufficient analytical software and data storage.

MIPVU evaluates the metaphoricity of single lexemes but in so doing misses the metaphoricity of larger word groups and their references. For example, MIPVU overlooks the metaphoricity of the famous nominal group “pale blue dot8.” When taken as a reference to the “dot” in the famous Pale Blue Dot image, the root noun “dot” and its larger nominal group “pale blue dot” are non-metaphorical, according to MIPVU. This is both because the nominal group is ignored, and the noun “dot” literally refers to the visible dot in the image. A DOT IS A DOT is not a metaphor.

However, at a larger textual level, the nominal group “pale blue dot” clearly refers to the earth through the image. THE EARTH IS A PALE BLUE DOT is the commonly invoked metaphor, even though MIPVU, strictly followed, would miss this. Consider also the following sentence from the dataset: “The issue with fossil fuels is that they involve burning carbon that was naturally stored in the crust over hundreds of millions of years as part of Earth’s process of counteracting the warming Sun.” “Fossil” and “crust” are identified by MIPVU as metaphorical, but this method misses the potential larger metaphorical constructions: concepts of nature, signaled by terms like “naturally,” “stored,” and “counteracting.” To make sense of the sentence, students must pull from their previous experiences with and concepts about nature, as well as the acts of storing (or stores of goods) and counteracting. Might students interpret the sentence through metaphors of agency (that is, NATURE IS AN AGENT), whereby nature intentionally and consciously stores things and counteracts forces to remain in an ideal state?

While analyzing the dataset, the researchers were continually confronted with the issues of determining where to delineate the lexemes. Polywords like “by now,” compound words like “two-tier,” and phrasal verbs like “blow up” are unclear cases that regularly frustrate the process. Steen et al. (2010) attempt to provide clear protocols for such situations, but the researchers still found them complex and opaque. Anyone attempting to use MIPVU for quick, surface-level analyses, like data from secondary school science teachers, are likely to become frustrated.

The final and perhaps most significant challenge was determining the most basic meaning of lexemes. Take, for example, the noun “record” from the nominal group “geologic record,” for which researchers were split in their identification of its most concrete, specific, human-centric sense meaning. Choosing from the Meriam-Webster Online Dictionary, is it: “1. To set down in writing”, or “3. To cause (sound, visual images, data, etc.) to be registered on something (such as a disc or magnetic tape) in reproducible form” (Meriam-Webster, n.d.)? This likely depends on the audience’s experience with vinyl records.

Adaptations

To help deal with the challenges in metaphor research we recommend three guiding principles: 1) create robust, phased analytic processes; 2) center the audience; and 3) follow MIPVU’s spirit, rather than its rules. It is especially important for those conducting rigorous linguistic studies to remain organized and systematic. We believe the phased process outlined in this paper to be a valuable tool in doing just this. By investing sufficient time and energy in establishing useful systems up front, much of the difficult cognitive effort in analysis can be reserved for the most important tasks, like identifying domains, main metaphors, and necessary pedagogic adaptations.

When identifying the contextual meanings, but especially the most basic ones, we recommend doing so according to the audience’s likely interpretations. The true locus of interest should be the students’ source domains, upon which they structure their interpretations of new concepts. It is important at this stage to aim to select the basic meanings students would tend to choose; this is achieved, ideally, by direct investigation, such as asking them which sense description they would choose. For example, what do they think of when they hear the word “record”? Based on this information, the teacher can identify the metaphoricity and relevant source domains of the term “geologic record,” tease out implications, and adapt educational techniques accordingly.

Outside of rigorous linguistic studies, most educators will have little time or use for strictly adhering to MIPVU’s arduous and complex rules or the phased process we have outlined here. Instead, we recommend most educators follow the spirit of metaphor analysis rather than its rules. This involves, most importantly, the following aspects:

- Appreciating—that linguistic metaphors are far more common than we realize, even in scientific language

- Recognizing—that linguistic metaphors influence the types of conceptual metaphors formed by learners

- Pondering—which source domains students are likely pull from when learning a new abstract concept

- Anticipating—how source–target mapping might align, or not, with the intended learning outcomes

Conclusion

In this paper we have outlined the process and preliminary findings of a project designed to identify and understand the metaphoric language used in a few chapters of a geoscience textbook. We have identified many key metaphors such as THE CRUST IS A CERAMIC PLATE, CONTINENTS ARE ICEBERGS, and NATURE IS A MACHINE. We have also described the structure of these metaphors including their relevant source and target domains, highlighted and hidden characteristics, and potential pedagogic consequences. Finally, we have also outlined our modified, simplified version of MIPVU for easier metaphor identification. It is our hope that this demonstration of our updated process will help both researchers and educators build more awareness of the language used to teach the many abstract concepts in science, including their pedagogic consequences and the potential of alternative metaphors.

Given the arduous nature of metaphor analysis, especially MIPVU and even our updated process, we implore educators to follow their spirit, not their rules. In particular, we encourage them to aim to pay special attention to the language use already around them. Many who begin doing this—often after reading Metaphors We Live (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980) or similar texts—are surprised to find that linguistic metaphors are far more common than they assumed, even in scientific language.

We also suggest including classroom activities that ask students to conduct a metaphor analysis themselves. Specifically, educators could ask them to identify MRWs and/or think about how certain conceptual metaphors used in scientific language function. What is the advantage of using this metaphor? What characteristics do these metaphors make most salient? What are they hiding? What other metaphors might better serve the desired concept?

Limitations

Given its early preliminary stage, this research has many limitations. So far, we have only analyzed a few chapters from a single textbook. Thus, the metaphors we identified here may not represent any sort of larger trend across the whole of introductory undergraduate (English) geoscience textbooks—even though they tend to align with previous studies. Additionally, the inherent complexity and interpretive nature of language, metaphor, and metaphor analysis mean others may likely interpret and identify metaphors differently than us. As mentioned earlier, individuals on our team differed on the most basic meaning of the verbal lexeme “record.” We assume that such differences are likely to occur for others. Finally, we have yet to check with students to see how they conceptualize these concepts and metaphors. Specifically, we do not yet know what source domains/concepts they are pulling from to construct target domains/concepts like “Earth’s crust” or “tectonic plates,”; we only know the likely sources. Nor do we know which source characteristics students will probably take as the most salient when constructing target concepts.

Future Work

We have only begun examining RQ1 and RQ2. For ongoing robust, nuanced, and reliable answers to RQ1 (What metaphors can we identify in an introductory geology textbook that would influence how students learn within that domain?) we plan to continue examining more texts using our current system. For greater examination of RQ2 (How might students understand geoscience concepts in light of the use of these metaphors?) we hope to conduct student observations, focus groups, and/or interviews. In this way, we should gain a better understanding of what sort of metaphors are commonplace in geoscience education and how these metaphors affect learning outcomes.

References

Amin, T. (2020). Coordinating metaphors in science, learning and instruction. In A. Beger & T. H. Smith (Eds.), How metaphors guide, teach and popularize science (pp. 73–110). John Benjamins Publishing.

Berger, A. (2016). Different functions of (deliberate) metaphor in teaching scientific concepts. Metaphorik.DE, 26, 61–86.

Boulter, C., & Buckley, B. (2000). Constructing a typology of models for science education. In J. Gilbert & C. Boulter (Eds.), developing models in science education (pp. 41–58). Kluwer Academic publishing.

Brown, T. L. (2020). Social metaphors in cellular and molecular biology. In A. Beger & T. H. Smith (Eds.), How metaphors guide, teach and popularize science (pp. 41–72). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Carey, S. (2009). The origin of concepts. Oxford University Press.

Cheek, K. (2012). Students’ understanding of large numbers as a key factor in their understanding of geologic time. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 10, 1047–1069.

Cheek, K. (2010). Commentary: A summary and analysis of twenty-seven years of geoscience conceptions in research. Journal of Geoscience Education, 58(3), 122–134.

Clark, A. (2011). Supersizing the mind: Embodiment, action, and cognitive extension. Oxford University Press.

Clement, J. J. (2008). Creative model construction in scientists and students: The role of imagery, analogy, and mental simulation. Springer.

Dodick, J., & Orion, N. (2006). Building an understanding of geologic time: A cognitive synthesis of the “macro” and “micro” scales of time. In C. A. Manduca & D. W. Mogk (Eds.), Earth and mind: how geologists think and learn about the earth (Geological Society of America Special Paper 413; pp. 77–93). Geological Society of America.

Dolphin, G., & Benoit, W. (2016). Students’ mental model development during historically contextualized inquiry: How the “tectonic plate” metaphor impeded the process. International Journal of Science Education, 38(2), 276–297.

Driscoll, M. (2005). Psychology of learning for instruction (3rd vol.). Allyn & Bacon.

Edwards, P. N. (2013). A vast machine: Computer models, climate data, and the politics of global warming. MIT Press.

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. The Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58.

Earle, S. (2019). Physical geology (2nd ed). Victoria, BC: BCcampus. https://opentextbc.ca/physicalgeology2ed/

Francek, M. (2013). Compilation and review of over 500 geoscience misconceptions. International Journal of Science Education, 35(1), 31–64.

Gardini, L., Grebogi, C., & Lenci, S. (2020). Chaos theory and applications: a retrospective on lessons learned and missed or new opportunities. Nonlinear Dynamics, 102(2), 643-644. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-020-05903-0

Grady, J. (1999). The “conduit metaphor” revisited: A reassessment of metaphors for communication. In J. P. Koenig (Ed.), Discourse and cognition: Bridging the gap (pp. 1–16). Center for the Study of Language and Inf; 73rd ed. edition.

Gilbert, J. K., Boulter, C. J., & Elmer, R. (2000). Positioning models in science education and design and technology education. In J. K. Gilbert & C. Boulter, J. (Eds.), Developing models in science education (pp. 3–17). Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Gruber, H. E., & Barrett, P. H. (1974). Darwin on man: A psychological study of scientific creativity. Dutton.

Indurkhya, B. (1992). Metaphor and cognition: An interactionist approach (Vol. 13). Springer-Science+Business Media.

Jackson, P. W. (2006). The chronologers’ quest: Episodes in the search for the age of the earth. Cambridge University Press.

Jadrich, J., & Bruxvoort, C. (2013). Confusion in the classroom about the natures of science and technology. In The nature of technology: Implications for learning and teaching (pp. 405-420). Sense Publishers.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow (1st ed.). Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Lakoff, G. (1993). The contemporary theory of metaphor. In A. Ortony (Ed.), Metaphor and Thought (2nd ed., pp. 202–251). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139173865.013

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1999). Philosophy in the flesh: The embodied mind and its challenge to western thought. Basic Books.

Marques, V., & Brito, C. (2014). The rise and fall of the machine metaphor: Organizational similarities and differences between machines and living beings. Verifiche, XLIII(1–3), 77–111.

Merriam-Webster (n.d.-a). Create. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved December 15 2022 from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/create

Merriam-Webster (n.d.-b). Record. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved December 15 2022 from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/record

Moore, K. E. (2014). The spatial language of time (Vol. 42). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Nersessian, N. J. (1985). Faraday’s field concept. In D. C. Gooding & F. A. J. L. James (Eds.), Faraday rediscovered: Essays on the life and work of Michael Faraday (pp. 377–406). Macmillan.

Nersessian, N., J. (2002). Maxwell and the “method of physical analogy”: Model-based reasoning, generic abstraction, and conceptual change. In D. Malement (Ed.), Reading natural philosophy: Essays in the history and philosophy of science and mathematics (pp. 129–165). Open Court.

Niebert, K., & Gropengiesser, H. (2015). Understanding starts in the mesocosm: Conceptual metaphor as a framework for external representations in science teaching. International Journal of Science Education, 37(5–6), 903–933. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2015.1025310

Niebert, K., Marsch, S., & Treagust, D. F. (2012). Understanding needs embodiment: A theory-guided reanalysis of the role of metaphors and analogies in understanding. Science Education, 96(5), 849–877.

Núñez-Oviedo, M. C., Clement, J., & Rea-Ramirez, M. A. (2008). Developing complex mental models in biology through model evolution. In J. Clement & M. A. Rae-Ramirez (Eds.), Model based learning and instruction in science (Vol. 2, pp. 173–194). Springer.

Norwick, S. A. (2002). Metaphors of nature in James Hutton's “Theory of the Earth with Proofs and Illustrations.” Earth Sciences History, 21(1), 26–45.

Pecher, D., Boot, I., & Van Dantzig, S. (2011). Abstract concepts: Sensory-motor grounding, metaphors, and beyond. In B. Ross (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 54, pp. 217–248). Elsevier Academic Press.

Petrie, H. G., & Oshlag, R. S. (1993). Metaphor and learning. In A. Ortany (Ed.), Metaphor and thought (2nd ed., pp. 579–609). Cambridge University Press.

Posner, G., Strike, K., Hewson, P., & Gertzog, W. (1982). Accommodation of a scientific conception: Toward a theory of conceptual change. Science Education, 66(2), 211-2278.

Pragglejaz Group. (2007). MIP: A method for identifying metaphorically used words in discourse. Metaphor and Symbol, 22(1), 1–39.

Rau, G., & Antink-Meyer, A. (2020). Distinguishing science, engineering and technology. In W. F. McComas (Ed.), The nature of science in science instruction Rationales and strategies (pp. 159–176). Springer.

Reddy, M. (1979). The conduit metaphor: A case of frame conflict in our language about language. In A. Ortony (Ed.), Metaphor and thought (pp. 284–324). Cambridge University Press.

Rohrer, T. (2005). Image schemata in the brain. In B. Hampe & J. Grady (Eds.), From perception to meaning: Image schemata’s in cognitive linguistics (pp. 165–196). Mouton de Gruyter.

Rout, M., & Reid, J. (2020). Embracing Indigenous metaphors: A new/old way of thinking about sustainability. Sustainability Science, 15(3), 945–954.

Rudwick, M. J. S. (2005). Bursting the limits of time: The reconstruction of geohistory in the age of revolution. University of Chicago Press.

Rumelhart, D. E. (1980). Schemata: The building blocks of cognition. In R. J. Spiro, B. C. Bruce, & W. F. Brewer (Eds.), Theoretical issues in reading comprehension (pp. 34–40). Routledge.

Shapiro, L. (2011). Embodied cognition. Routledge.

Steen, G. J., Dorst, A. G., Herrmann, J. B., Kaal, A. A., Krennmayr, T., & Pasma, T. (2010). A method for linguistic metaphor identification: From MIP to MIPVU. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Strike, K., & Posner, G. (1992). A revisionist theory of conceptual change. In R. Duschl & R. Hamilton (Eds.), Philosophy of science, cognitive psychology, and educational theory and practice (pp. 147–176). State University of New York Press.

Thibodeau, P. H., & Boroditsky, L. (2013). Natural language metaphors covertly influence reasoning. PLoS ONE, 8(1), e52961.