Final Report Synthesis: Addressing Misconceptions Around Magnitude and Intensity to Inform Earthquake Early Warning Alerting Stragegies

ADDRESSING MISCONCEPTIONS AROUND MAGNITUDE AND INTENSITY TO INFORM EARTHQUAKE EARLY WARNING ALERTING STRATEGIES

FINAL REPORT SYNTHESIS

Synthesis compiled by Dr. Glenn Dolphin

Department of Earth, Energy, and Environment

University of Calgary

Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Executive summary and recommendations

Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) is implementing an Earthquake Early Warning (EEW) alert system in April 2024. The purpose of the EEW system is to alert the public of an impending earthquake so they can take appropriate measures to protect themselves from possible injury or death. By observing other countries that have implemented such a system, especially the United States (whose ShakeAlert® system is the model for the Canadian EEW system), it is obvious that just pushing out a warning to the public does not achieve the desired effect of the public taking appropriate protective actions such as drop, cover, and hold on (DCHO).

There are several prerequisites which must be met before a person receiving an EEW alert will take the appropriate protective actions. This research revolves around one of those prerequisites, peoples’ understanding of two different concepts: earthquake intensity and earthquake magnitude. These two concepts are important because they form the basis for determining when and if a person receives an EEW alert. Trust in the system is another prerequisite for proper response to an alert. For people to maintain trust and avoid user fatigue, understanding why they did or did not receive an alert is crucial. Having a working concept of earthquake intensity and magnitude would go a long way toward reaching this goal.

To complete a comprehensive study of how people understand intensity and magnitude, why they are understanding it this way, and how to enhance peoples’ understanding to be closer to the consensus view required us to approach the problem from three different directions: historical, linguistic, and sociocultural. The results of this work appear in the ensuing chapters of this Final Report Synthesis (De Jong, 2024a, 2024b, 2024c, 2024d, 2024e; 2024f; Droboth & Dolphin, 2024; Muturi & Dolphin, 2024).

Results of the historical case study emerged as a historical case study of the concepts of earthquake intensity and magnitude, kind of like a conceptual biography. This case study helped us to see how:

- Developments in understanding of earthquakes, intensity, and magnitude often happened after a large and destructive event.

- Conceptual understandings also followed closely behind technological developments.

- Intensity scales developed in response to a need to describe or characterize earthquakes.

- Characterization of earthquakes via intensity scales did not allow for direct comparison from one event to another.

- Richter magnitude resulted from the desire to characterize earthquakes in a way where direct comparisons from one even to another could be made.

- Moment magnitude became that universal characterization, being a measure of work done or energy released during an earthquake.

- There is a paradox where intensity is a very concrete concept as it is the shaking and the destruction we can physically experience about an earthquake, yet we consider it abstract because it is subjective. Intensity depends on where you are with respect to the earthquake. At the same time, magnitude is considered a concrete value because it is an absolute value, regardless of where you are with respect to the epicenter. It represents energy released, and energy is a very abstract concept.

These things we learned help us to understand the concepts better and how we should go about informing the public about them (See recommendations below).

The second approach, the linguistic approach, encompassed analyzing the United States. Geological Survey’s (USGS) ‘Did You Feel It?’ (DYFI) dataset. Data came from events in both the United States and Canada, and on both western side and eastern side of North America. We have discerned from the data that:

- Most respondents understand the concept of intensity, intrinsically, in that they understand that their experience of the shaking is personal and will not be like anyone else’s experience. However, they do not necessarily equate this embodiment to the actual word, intensity.

- The respondents recounted iterations of thinking in the process of making sense of the shaking they were experiencing, until they finally realized it was an earthquake.

- Many respondents, once settling on the notion they were experiencing an earthquake took no protective action. They either tried to connect with someone, or they just stayed still.

These results also help us to think about the kinds of educational interventions that would be effective to first, interrupt the iterations of meaning making and second, help the public take the appropriate protective actions. From the data, it appears that just knowing there is an earthquake is not enough to get people to act in a way that will minimize harm, however, it can help to get them in a proper state of mind where the next logical step is to take protective action.

Finally, we used a sociocultural approach to understand better the capability and capacity of the earthquake science education ecosystem. This step has helped to identify and analyse how the Canadian earthquake science education ecosystem creates specific vulnerabilities for the EEW system. To illustrate, many Canadians rely on ad hoc volunteerism to deliver earthquake science education which creates more vulnerability for the EEW system. They lack financial and human resources capable of providing content to Canadians with content relevant to the EEW. Thus, there is a need to explore this opportunity, yet consider the longer-term implications of this dynamic.

From our research, it seems most people have a favorable idea of EEW systems and that the alerts do not necessarily result in recipients taking protective actions, the alerts prepare them to do so (this is supported in the DYFI data analysis). The socio-cultural approach also led us to the many resources–most of them online–where people might seek out information about these concepts. We developed tools and techniques to evaluate these resources to find there are inconsistencies that lead to the stakeholders’ misunderstandings of intensity and magnitude. Since the EEW alerts need to work in concert with stakeholders to 1. maintain trust and confidence in the EEW system, and 2. Instigate appropriate protective actions, it is imperative to: a) have the tools and techniques to evaluate he resources relevant to the EEW earthquake science education; b) ensure the content is relevant to the EEW site to site among governmental and association websites and resources. The Government of Canada needs to better support the EEW in this endeavour.

We developed tools and techniques to evaluate these resources to find there are inconsistencies that lead to the stakeholders’ misunderstandings of intensity and magnitude. Since the EEW alerts need to work in concert with stakeholders to 1. maintain trust and confidence in the EEW system, and 2. Instigate appropriate protective actions, it is imperative to: a) have the tools and techniques to evaluate he resources relevant to the EEW system earthquake science education; b) ensure the content is relevant to the EEW site-to-site among governmental and association websites and resources. The Government of Canada needs to better support the EEW system in this endeavour.

1.0 Introduction to the research

Canada is currently in the implementation phase for a national earthquake early warning system (EEW) that will operate in regions including British Columbia, and Ontario, Quebec, and New Brunswick in the east. To ensure effectiveness of EEW alerts, the public needs to understand the alert message when they receive it and immediately know what to do, such as “Drop, Cover, and Hold On”. A challenge with EEW broadly is to avoid end-user fatigue while maintaining system confidence. Maintaining these goals is not limited to the system and its operations, but also with how the public interprets the alert, especially as alerts are continually tested and fine-tuned (McBride et al., 2020).

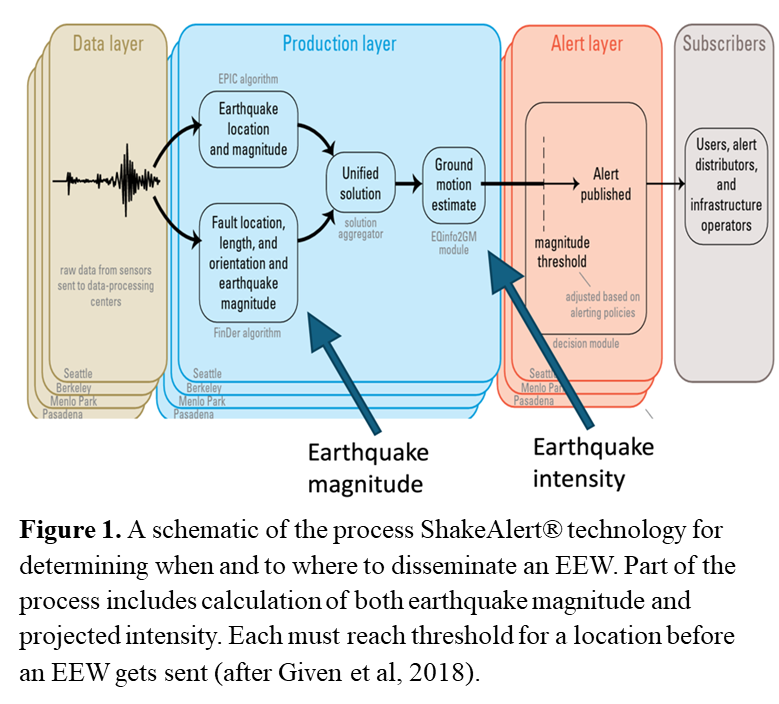

The Canadian EEW system is based on technology already implemented in the United States by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) called ShakeAlert®. ShakeAlert® depends on the quick detection of the P-wave and calculation of an earthquake’s location, magnitude, and intensity (Figure 1). If an earthquake above a certain magnitude threshold is detected, the goal is to send an alert out to potentially affected communities who may feel shaking above an intensity threshold before the S-wave is felt (Given et al., 2018). The USGS finds that various members of the public have difficulty understanding when and why they receive an alert and explaining the situations in which they do not, which therefore requires post-alert messaging (McBride et al., 2020). A major reason seems to be a lack of public understanding around earthquake magnitude and intensity. These terms are commonly used in everyday lexicon yet have very specific scientific meaning in seismology. It is important that the EEW system users have reliable understandings of these concepts because the end-user response to the system relies on reaching specific intensity and magnitude threshold criteria prior to generation of an alert.

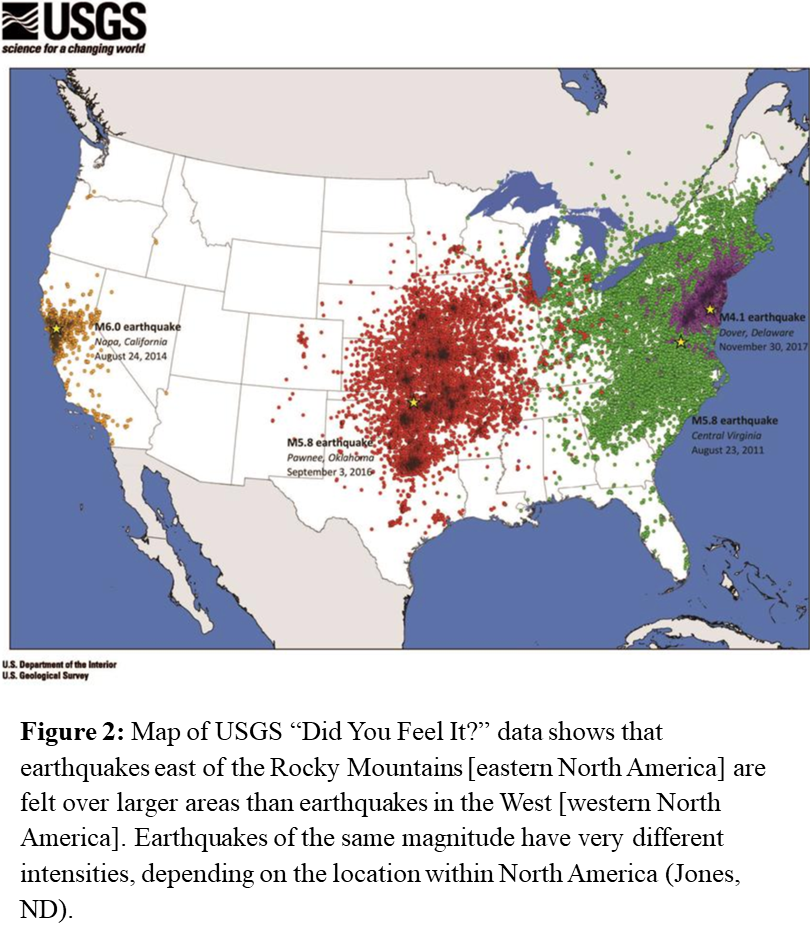

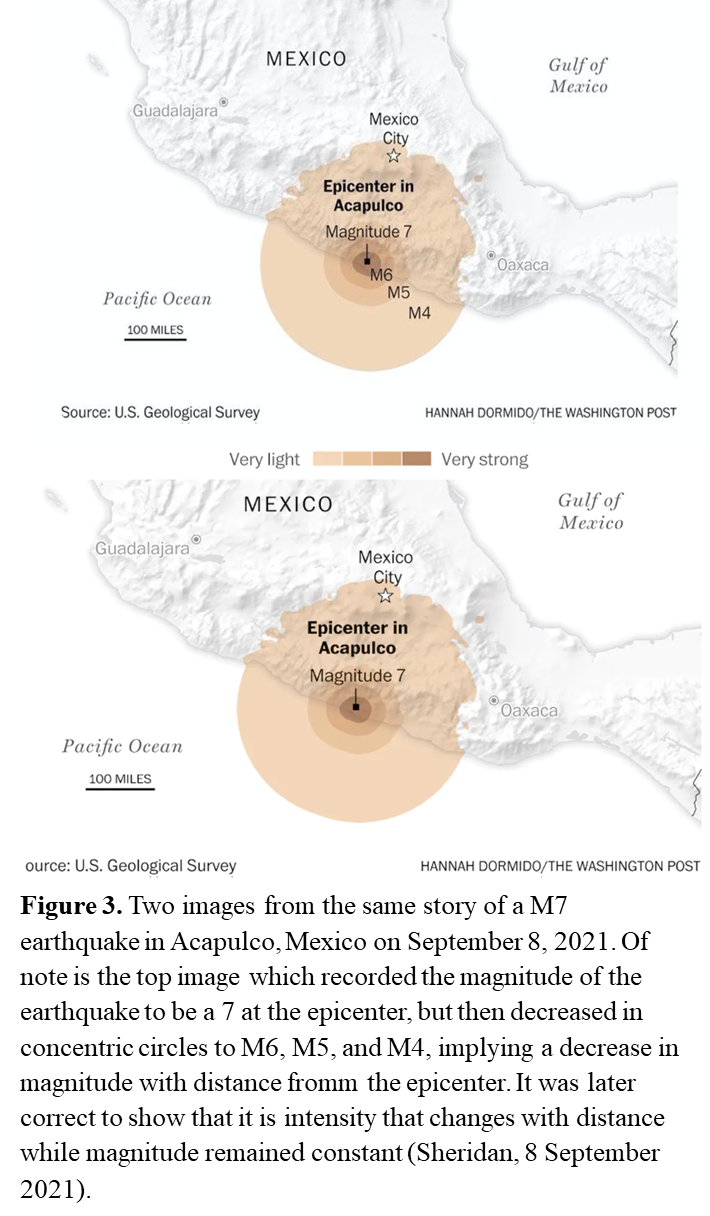

The Canadian EEW system will reach along both eastern and western provinces, and because of the difference in geology between these two regions, the same magnitude earthquake will produce very different intensities (Figure 2). The USGS uses the saying “Fewer quakes but bigger stakes in the east” because earthquakes in eastern North America are more widely felt than earthquakes in the west (Jones, ND). In addition to the difference in intensities between eastern and western North America, there is evidence of a general confusion (and oftentimes conflation) of the meanings of intensity and magnitude (e.g., Figure 3). Thus, the development of the Canadian EEW system must address education and communication around earthquake intensity and magnitude, because these concepts relate directly to when and why people receive early warnings and therefore can help maintain trust in the EEW system for the long-term.

Addressing this problem will require a strong public education initiative, one that will reach all potential end-users of the EEW system. Our project was to visualize the potential scope of the educational initiative and included students and faculty from the University of Calgary, the USGS, the EarthScope Consortium, and James Madison University. Our investigation enacted a three-pronged approach to specifically address the earthquake intensity and magnitude question, a historical approach, a linguistics approach, and a socio-cultural approach. Researchers have developed a knowledge base to inform the EEW system at the interface of the EEW system and the public in Canada. The Calgary team worked to discover why public understanding of these scientific concepts (intensity and magnitude) does not reflect the scientific consensus, and how to best mitigate the issue(s) through appropriate education and communication strategies. We use the information gathered to help us understand what needs to be done prior to alerting, what the alert should contain, and how any post alert messaging should entail.

2.0 The Three-Pronged Approach

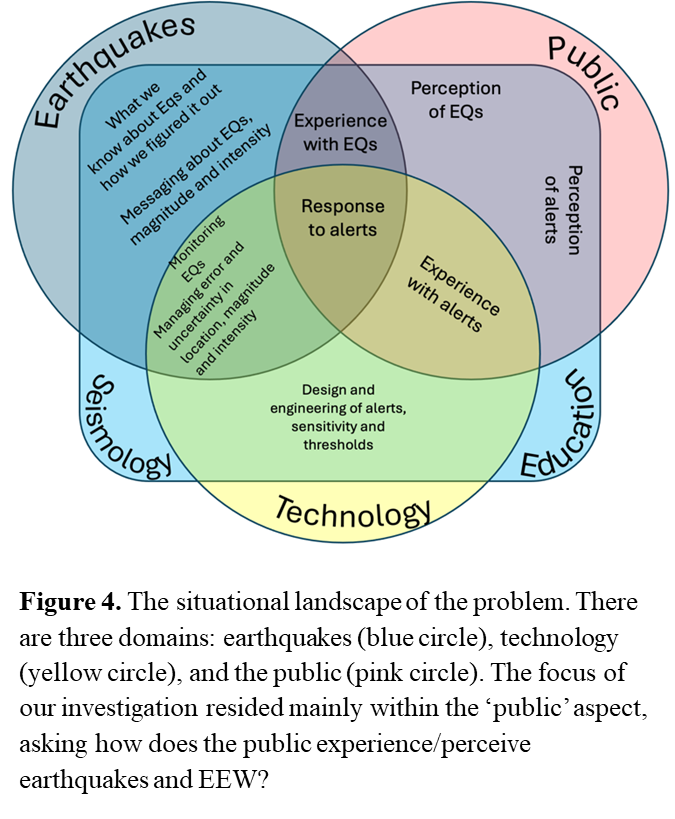

The problem of understanding how the public perceives earthquakes and understands concepts like intensity and magnitude, and how they understand earthquake early warnings is very complex. There are many variables at play, so the investigation team thought that it would make sense to look at different aspects of the problem. We surveyed the situational landscape and parsed the problem into four different but overlapping domains, the natural world (earthquakes), the technology (EEW system), the public (perceivers of earthquakes and receivers of the EEW alerts) and the knowledge we have about each of these domains (seismology education). There is a great deal of science learning and understanding by geologists and geophysicists on the part of the earthquakes in the natural world. There are computer scientists and engineers working on technology for creating an EEW system that is responsive and reliable. This leaves understandings by the public. Our focus became developing an understanding about how the public perceives the phenomenon and how they perceive the EEW system, as well as understanding the public’s experiences with both. All of this is encompassed in the system of seismology education about the phenomenon, the technology, for the public (Figure 4). We wanted to know how the public understood these concepts (intensity and magnitude), how they developed those understandings, and what we could do to influence the public’s understanding in a direction conducive to taking appropriate protective actions after receiving an EEW alert. Getting to the answers to these questions required three lines of inquiry; historical, linguistic, and sociocultural.

2.1 Historical Approach (Muturi & Dolphin)

The use of the history of science to teach science and about science began in the mid 20th century (Conant, 1947). The reason is that with the history of science, students can also learn about the process of science (Matthews, 2015). One effective vehicle for introducing and using the history of science for teaching science is the historical case study (Allchin, 2011; Dolphin et al., 2018). Using historical case studies gives students the opportunity to experience science-in-the-making (Latour, 1987) and help them to develop more reliable mental models of target concepts (our goal). Learners use the case study to develop their model of the target concepts similar to how the original scientists did, highlighting the rationale for the model, and giving the learner a stronger foundation for their understanding. Using this approach we have come to understand the historical development of the concepts of earthquake intensity and earthquake magnitude, and we have developed a case study which addresses this development directly for use as a teaching strategy (Muturi & Dolphin, 2024).

The case starts with the with the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, the case shows how our understanding of the earthquake phenomenon and the concepts of intensity and then magnitude progressed with each subsequent big event and new technological advancements, which allowed us to perceive the earth and its signals in ways we could not do with our human senses. There was an effort to characterize each earthquake based on the damage each caused, but this did not allow for direct comparisons of one event to another. As the need to compare one event directly to another developed. These early lines of inquiry, including the technology developing in tandem, culminated in intensity scales that helped document the damage caused by each earthquake, and how the scope of that damage changed with distance from the earthquake epicenter as well as the nature of the geology below the area the earthquake affected.

As it became obvious that scales of intensity would not allow for meaningful comparisons of one earthquake to another Charles Richter began trying to solve this problem. His fascination with astronomy led him to consider magnitude of an earthquake to be like absolute magnitude of a star. Absolute magnitude of a star is the brightness of a star compared to other stars if an observer is seeing all stars from the same distance away. Richter set about graphing seismicity data and calculating maximum seismic wave amplitudes (the analogue to star brightness) from a standard distance from the observer.

Using both primary and secondary sources, the historical case study tracks the events and people involved in developing these conceptual understandings. The case has an “interrupted case” structure (Herreid, 2007; Hodges, 2005), incorporating periodic pauses in the narrative that allow the reader time to consider and reflect upon the knowledge development as it is taking place in the narrative. Readers come to realize the coupled relationship between technology and scientific understanding. They also develop notions about scientific knowledge within the context of reliability, as opposed to truths that are ‘certain’.

2.2 Linguistic Approach (Droboth)

Work in the field of cognitive linguistics (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980, 1999) and embodied cognition (Clark, 2011; Shapiro, 2011) demonstrate that most of our understanding–and therefore, our communication–is metaphorical, with its basis in concrete sensory information. Importantly, metaphors are effective because they highlight certain aspects of the target concept. However, they also hide aspects. Novice learners, who think differently about scientific concepts than experts (Clement, 2008) are less likely to discriminate between what is highlighted and hidden–what they should pay attention to and what they should not–and therefore can develop understandings about the target concept that do not match intended meaning.

For instance, Dolphin and Benoit (2016) found that the tectonic plate metaphor was inhibiting students’ understanding of earthquake occurrence because their experience with plates was not as large portions of the earth’s lithosphere, but as ceramic dinner plates, which they considered as separate and brittle. This caused them to think that earthquakes happened when tectonic plates were pushed together and collided.

Understanding how concrete experiences influence how we think of abstract concepts through the use of metaphor can then help us direct thoughts of learners better (Amin, 2015; Beger & Smith, 2020). For instance, in the example just given, Dolphin and Benoit (2016) generated a new metaphor, the lithosphere is the skin of the earth. In this case, the skin is the source for the metaphor projected onto the target, lithosphere. This metaphor highlights the wholeness of the lithosphere of the earth and its elastic properties. Importantly, everyone has had many concrete experiences with their skin. They can also use shearing, compressional, and to some extent tensional forces to produce analogous deformation on their skin.

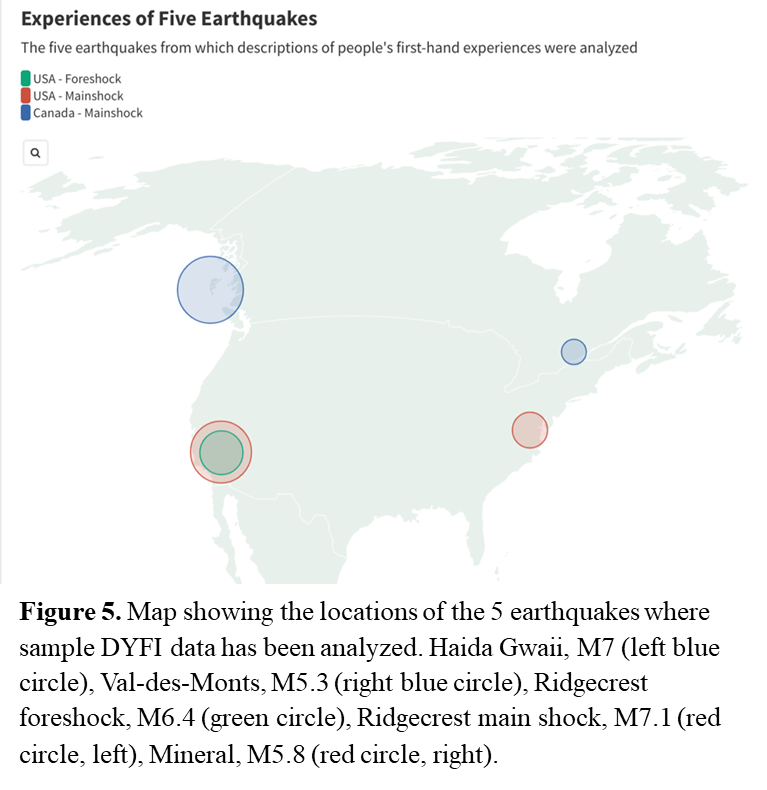

To see how the public spoke about earthquakes, and whether their metaphors might inform us how they are thinking about earthquakes, we have done a systematic analysis of the USGS ‘Did You Feel It?’ (DYFI) open-ended survey questionnaire data. The DYFI data came from five different earthquakes (Haida Gwaii, BC, M7; Val-des-Monts, QC, M5.3; Ridgecrest, CA, foreshock, M6.4; Ridgecrest, CA, main shock, M7.1; and Mineral, VA, M5.8) (Figure 5). To our knowledge, this is the first time anyone has done systematic analyses of the responses to the questionnaire. The results have been enlightening and we categorized them into three main categories: how respondents described earthquakes, the metaphors respondents used associated with earthquakes, and respondents cognitive processing of earthquakes. Researchers used a grounded theory approach to analyze over 1,000 excerpts from the DYFI data of the five different events. These data allow us to infer how the respondents were thinking while they were experiencing their respective earthquake and to better understand possible strategies to help the public take intended protective actions in the event of an EEW alert (Droboth & Dolphin, 2024).

2.2.1 How respondents describe earthquakes

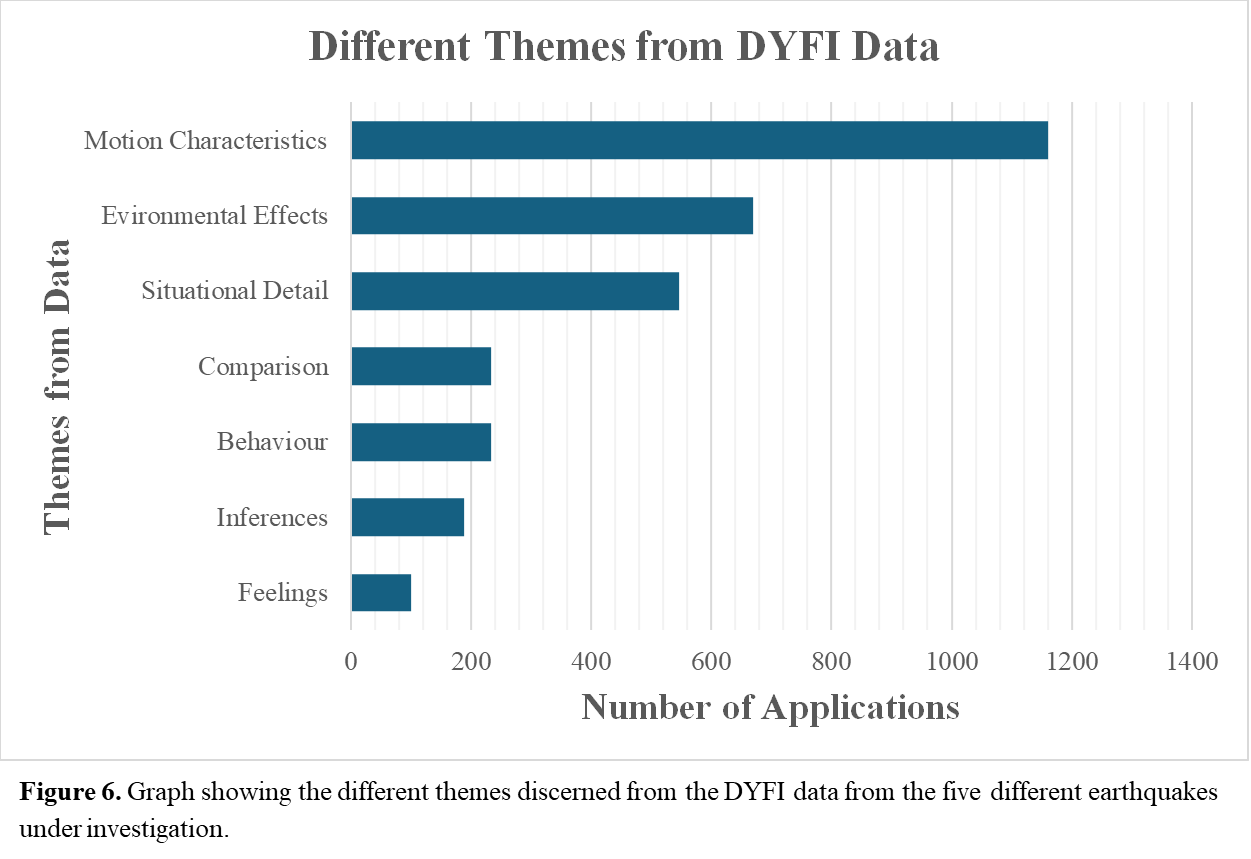

When reading DYFI responses for the different samples of earthquakes, we discerned 7 major themes that respondents expressed that help us to understand how they are thinking about earthquakes (Figure 6). Based on the data, there were seven major themes from the open-ended responses from people reporting about the earthquake they were experiencing.

- Motion characteristics describes how respondents were perceiving the motions caused by the earthquake they were experiencing. Within this theme were descriptions about the types of movement, like swaying/swinging, or rocking/rolling. They also described the strength, duration, and even direction.

- Environmental effects refers to the impact on the immediate environment from the shaking. Respondents described such things as water or other item movement, any sounds related to the movement and what damage may have been caused. There were also descriptions about animals’ (mainly pets) behaviour before, during, and after the event.

- Situational details mainly dealt with the environmental context of the respondent during the event. These would be descriptions of the respondent’s posture (standing, sitting, lying down), where they were geographically, the kind of building they were in, and on what floor, and what they were doing when the event started.

- Comparison gives an indication of how the respondents considered the earthquake in terms of other experiences they have had, like other seismic events ore events that were not seismic in nature, how they experienced the earthquake compared to other people they know, or compared to how they experienced a past event.

- Feelings was the respondents reporting on the emotions they experienced during and immediately after the event. This included feelings of confidence if they had already experienced multiple prior events, or confusion, dizziness/nausea, excitement, fear, or intrigue.

- Behaviours are the descriptions respondents gave of what they did during and right after the event. Mostly, respondents tried to connect with others to see if they were experiencing the same thing. Some sought official information or evacuated their building. Many just stayed in place, while others moved to a doorway. Some assisted others, and a very small percentage of respondents described that they took the protective action, drop, cover, and hold on. This, of course is what we would like to have happen for everyone.

From the data we interpret that there is a lot going on with people experiencing an earthquake, from trying to make sense of their perceptions, the feelings they had prior to and as they came to understand what was happening, and then what they did because of that generation of understanding. This is the crucial time, becoming aware of the situation, not panicking, and having the mindset, or confidence to take appropriate protective action. We will further flesh out this idea in 2.3, below.

2.2.2 Metaphors respondents use associated with earthquakes

We also looked at the text using a conceptual metaphor theoretical framework (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980; Niebert & Gropengiesser, 2015). In this way, we could record the incidental metaphors respondents used to develop further insights into how respondents were thinking about their experiences. We recorded one major metaphor used by respondents. When they talked about the waves of an earthquake, or seismic waves, they did so in terms of ocean waves, or waves in the water that would rock a boat. Rayleigh waves do produce motions coherent with that of waves traveling across the surface of water, in an up and down/back and forth motion. This association puts something unknown (seismic waves) into terms of something that is known (ocean waves) that could help ground the person experiencing an earthquake and allow them the comfort to then start thinking about how to react.

Information such as this is important when thinking about how to alert the public and give them the information they need to have an accurate assessment of what is going on and then what to do in that case. The earlier the public is aware of what is or what will happen the more time and confidence they have for taking proper protective actions. We explore this idea further in the next section.

2.2.3 Respondents’ cognitive processing of earthquakes

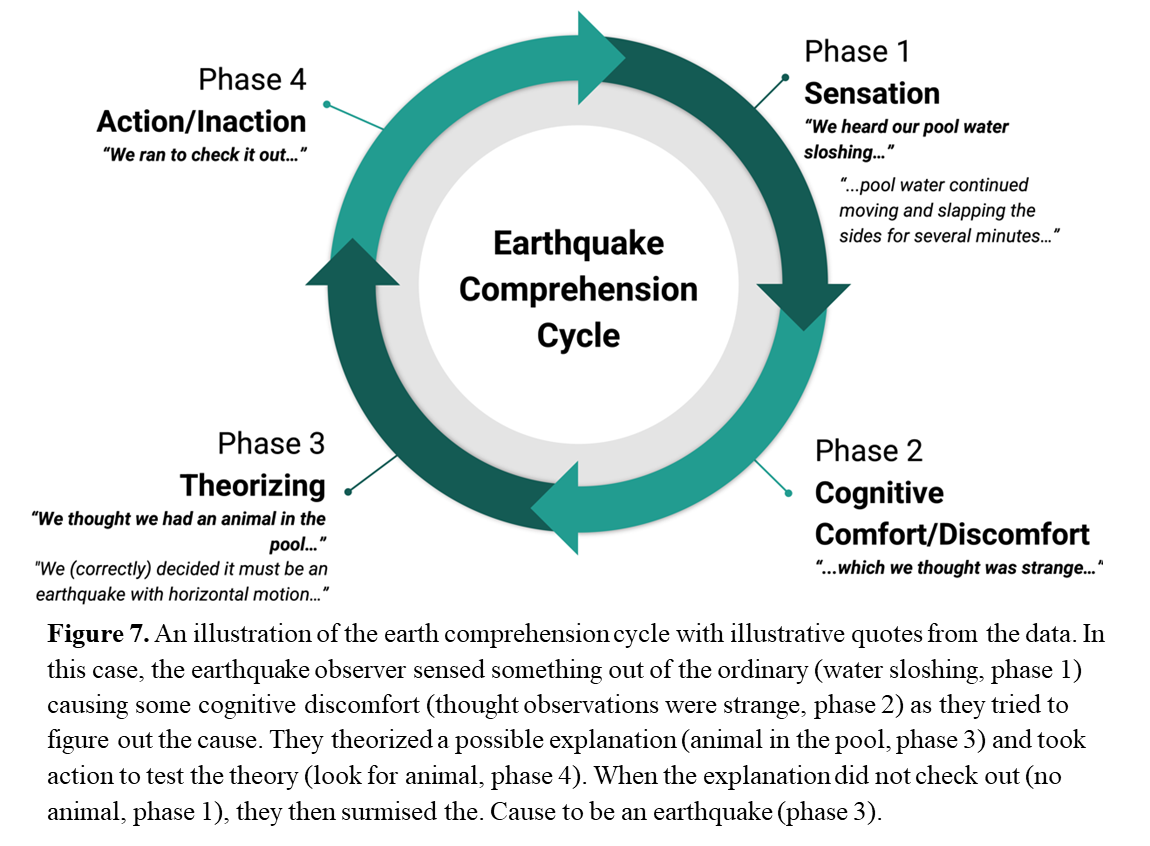

Where responses were long enough and detailed enough, we were able to discern a pattern regarding the respondent’s cognitive processing of the earthquake phenomenon they were experiencing. The processing occurred as a iterations of thinking until comprehension was resolved. We have identified this as the Earthquake Comprehension Cycle (Figure 7).

The cycle starts with Phase 1, the perception of the earthquake, or some other effect of the earthquake that causes cognitive dissonance in the observer. In Figure 7, this is where the respondent described observing the water in their pool sloshing. Phase 2 is when the respondent expresses the dissonance (“That was strange.”). Then the respondent tries to make sense of the observations by theorizing (Phase 3) that there might be an animal that fell into the pool. After, they took an action (Phase 4) and went to look to see if there indeed was an animal in the pool. When they did not see an animal (Phase 1), they again questioned (Phase 2) what the cause might be. They finally settled on the idea that it must be an earthquake (Phase 3).

This cycle is coherent with other research such as Neisser’s (1976) perceptual cycle model and Rehorick’s (1986) phenomenological model. This finding is important because an EEW alert can circumvent the cognitive dissonance (Phase 2) of the cycle, and send the public right to Phase 3 and 4, maybe even before the shaking starts, then the people will have the time and confidence and hopefully the training to take immediate and appropriate protective actions.

The aspect of training for taking appropriate action is important. Our data show that even when respondents realized they were experiencing an earthquake, they often remained still and did NOT take any protective actions. To a lesser extent respondents ran to a doorway or simply evacuated their building. Alerting people early about an imminent earthquake can put them in the proper mind set, but unless the people know what the appropriate actions to take are and have practiced them, they will not take them.

2.3 Sociocultural Approach (De Jong)

Many other regions of the world experience high occurrences of earthquakes and have developed their own tactics and strategies for lowering the risk to property and life. One of the strategies for some countries includes the implementation of EEW systems. As EEW have gone online internationally, colleagues in Mexico and Latin America have also expressed misconceptions around earthquake magnitude and intensity (Sumy, pers. comm., 2021). Understanding how these other regions have approached the problem, and the efficacy of those approaches would be invaluable to formulating our own processes here in Canada. For instance, Japan has implemented their own EEW system based on an algorithm called PLUM (Propagation of Local Undamped Motion; Kilb et al., 2021) that places emphasis on earthquake intensity over magnitude and is currently under consideration for the USGS ShakeAlert® project. Japan has taken a multi-faceted approach to educating their public to know what to do in the event of an earthquake, and their education places much more emphasis on earthquake intensity instead of magnitude (Aoi et al., 2020). This is unlike North America, which has the emphasis reversed. We have conducted a literature review as a means for investigating areas using EEW systems and understanding their public’s perceptions of the EEW system. We have also analyzed the history and status of earthquake and seismic education across Canada and conducted the first bi-lingual, trans-Canadian survey to develop a benchmark of the public’s understanding of earthquake intensity and magnitude. A summary of these projects occurs below.

2.3.1 Summary of perceptions of EEW systems and how they impact behavior

Though Canada is a context all its own, it is helpful to look to other regions experiencing similar circumstances to inform our observations and guide our theorizing. We will make four main points that result from the literature review about peoples’ perceptions and behavior of EEW system alerts (Bellizzi, 2023).

- The public’s experiences directly with EEW systems impact the overall trust, negatively or positively, in EEW systems, and trust is a critical component for people understanding and taking protective actions recommended in the warning message,

- Across different cultures, public perception of EEW system is overall positive,

- The public’s experience with EEW systems shows that EEW systems do not significantly influence public behavior during an earthquake but rather has helped people prepare mentally (see results in section 2.3 above), and

- Understanding the psychological nature of dominant response and its interaction with EEW alerts can help government entities better message and educate the public they seek to serve with EEW.

What we have found also supports the observations we have made in our research of the Canadian context. The pan-Canadian survey (see below) reinforces the notion that perceptions of an EEW system is a positive thing (point b, above). Also, that the public looks toward the government for education about the messaging but also about what actions to take when getting an alert (point d, above). Our analysis of the DYFI data also echoes point c, above. The messaging is not enough to trigger appropriate protective actions, but rather sets the stage for taking protective actions by bringing about a sense of confidence in the public that they know what they are experiencing (or what they will be experiencing). A comprehensive education plan for the public concerning what to do next is paramount to facilitating the public to take appropriate protective actions such as DCHO.

2.3.2 The bi-lingual, pan-Canadian Earthquake Education Survey

During February to April of 2023, we engaged with the public to respond to our recently developed bi-lingual, pan-Canadian survey on earthquake education (de Jong & Dolphin, 2023). The purpose of the survey was to collect data regarding the understanding of the state of the public conceptions and education related to earthquakes as well as the Canadian EEW system. We included questions about the concepts of earthquake intensity and magnitude, and we also included questions concerning perceptions of EEW system and hazard risk communications and education. The survey contained 19 open-ended questions on earthquake content (i.e., What is an earthquake? What causes and earthquake? Is there a difference between earthquake magnitude and intensity?) and hazard risk communications and education (e.g., What are some of the best resources for learning about earthquakes? If you had a minute after receiving and alert before shaking begins, how would you spend that minute? What needs to happen before you feel comfortable that you can react to an EEW alert confidently?). There were another five on demographics and asking if participants wanted to be contacted for follow-up reports on the results of the research.

We published the survey in Qualtrics® within the University of Calgary, in both French and English. We announced the availability of the survey to various geological and hazard risk associations with the country and promoted the spread by word of mouth. The survey. Was available from early February to end of April in 2023. We had almost 500 respondents, 182 French and 315, English. We had the French open responses translated into English prior to formal analysis. Though there seem to be some subtle (and not so subtle) differences in answers between the two populations, we will give some preliminary analysis as a single group of respondents.

2.3.2.1 Survey data analysis methodology

We used a phenomenographical framework as a theoretical and analytical framework. Phenomenography is a framework that guides the analysis in terms of how a group of participants understands a phenomenon––as opposed to separating out each individual participant’s understanding. It does not look at meaning-making at the individual level, as is often the focus and product of qualitative research. Instead, phenomenography begins with these key assumptions (Stokes, 2011):

- People have varying conceptions of the same phenomenon because they experience that phenomenon differently from other people.

- People can express their conceptions of the experienced phenomenon through verbal or written expression.

- A finite number of conceptions exist for any one phenomenon.

- Different conceptions can be organized hierarchically, from general to specific.

Starting with these assumptions, the researcher sought to discern an account of how a group of respondents understand a phenomenon. For individuals, reality is based on how they experience or conceive of that reality and their descriptions follow this (even if this is not consistent with how reality may be). Instead, against this background, phenomenography aggregates the individual descriptions of reality held within an entire group to report a holistic or collective understanding (Hajar, 2021).

We imported the survey data into Dedoose®, a cross-platform app for analyzing both qualitative and quantitative data, and using an open coding approach, began to develop codes for the nearly 20 responses for each of the 500 participants. Open coding means the researcher develops the codes based on the repetitions of important ideas within the responses. There was not a list of expected response codes, they were made up as the analysis progressed.

2.3.2.2 Findings

The following represents a sample of the data analysis. We will display data concerning the conceptual understanding of the respondents around earthquakes and magnitude and intensity. We will also provide data from respondents that help us understand their needs in terms of information and information sources.

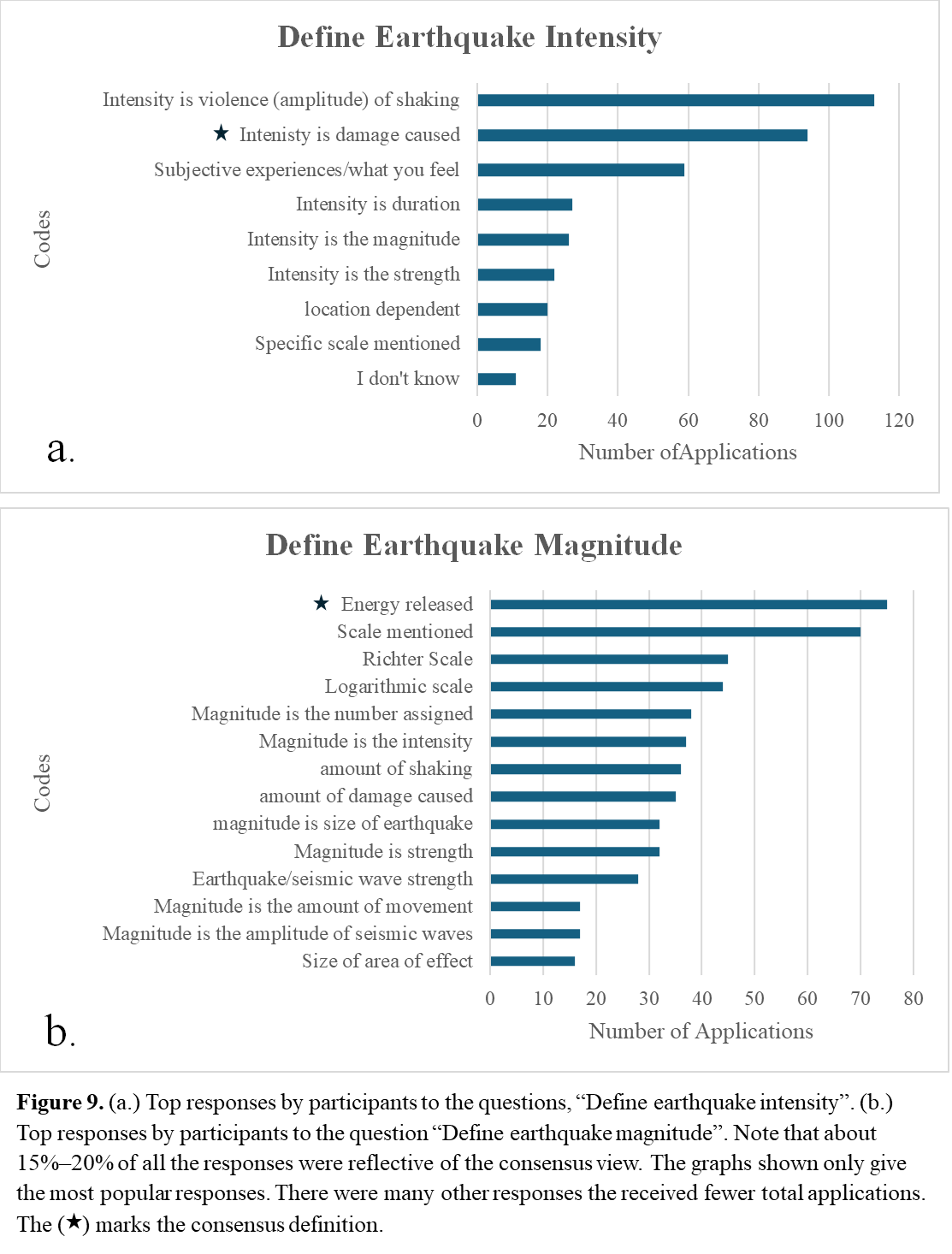

When asked if they thought earthquake magnitude and intensity were the same thing or different, most respondents (210/295) agreed that they were different concepts. However, when asked to define the two, there were many different answers that were not coherent with the consensus view. Ninety-four respondents (about a third) supplied a definition that reflected the consensus view, “Intensity is the damage caused”. A smaller number of respondents, 75, defined magnitude in a way coherent with the consensus view. Many also associated magnitude with the Richter Scale, and a logarithmic scale. Our assumption has been that since this survey spread mainly thorough earth science education and hazard risk management associations and organizations, those responding would have a better than average understanding of earthquake intensity and magnitude. By looking at the variety of the responses, it should also be obvious that many conflate the two concepts, and also that many understand intensity as something that a person feels and is determined by where they are with respect to the epicenter, and that magnitude is a number assigned, is logarithmic, and is the same no matter where the observer is standing.

There are a few other important findings from the survey data that can help inform those interested in maximizing effectiveness of the EEW system alerts. Almost half of the respondents knew that Canada’s west coast is highly susceptible to earthquakes. To a lesser extent (150/500), respondents also correctly identified the eastern provinces as susceptible as well. They knew the hazard to some extent and where one is more likely to occur. They have a rudimentary understanding of what an earthquake is (release of energy, 60 responses) compared to ground shaking (182 responses). They also mainly put earthquakes in a plate tectonics framework when responding to “What causes an earthquake?”, with “movement of crust or plate” (245 responses), or “collision of plates” (54 responses) with some also identifying “volcanism” (16 responses) and “hydraulic fracturing” for fossil fuels (46 responses) as other mechanisms.

In addition to the geological concepts, we asked some questions about the implementation of the EEW system and education about earthquakes and about the EEW system and alerts. These responses can help inform NRCan and other related government agencies where to focus efforts when thinking about how to best prepare the public. When asked what they would need to feel comfortable when responding to an alert, respondents pointed to educating the public about earthquakes, and about the EEEW system (160 responses). They thought that awareness and planning for such a hazard was also important (62 responses), and that some sort of organized practice or drills of protective actions should take place (50 responses). A few respondents mentioned the Great ShakeOut (Statewide California Earthquake Center, 2024). Many indicated the need to overcome public apathy, disinformation, and conspiracy theories.

Another important insight received from survey data analysis was that respondents were generally excited about the prospect of the EEW system implementation. They indicated interest in learning about the system and relayed that mostt would rely on government agencies to receive the information about earthquakes and the EEW system (211 responses), and then other internet websites (122 responses) and universities and other experts (59 responses). This is important to know because it shows the importance of government agencies (NRCan, Earthquakes Canada, etc.) to maintain current, accurate, and coherent (between all agencies) information.

2.3.3 Global visual inventory of earthquake education lessons

Visual content has become an increasingly popular medium as increasing numbers access the internet with mobile devices. For this reason, it is important to be able to find and evaluate for their pedagogical value. To accomplish this, we have developed some tools to use in tandem with those already in existence. The tools are:

- Typology of visuals for earthquake science education: Rapid classification from a pedagogical perspective

- The art of earthquake intensity and earthquake magnitude: A research-based checklist for critique of visual content.

The three analytical tools are used to identify and make transparent commonly held earthquake magnitude and earthquake intensity misconceptions. Combined, they provide a systematic evaluation of different visual content, thus making transparent methodological errors in providing messaging content. This method could become an effective intervention for addressing misconceptions and improving practices of understanding earthquake science. This method seeks to ensure fit for purpose EEW relevant earthquake science communication is available for new and diverse audiences (De Jong, 2024b)

2.3.4 Answers to 10 significant questions about common misconceptions of earthquake intensity and earthquake magnitude

Significant research has been completed in an effort to understand how the earthquake science concepts earthquake magnitude and earthquake intensity can be misunderstood in the context of a crisis communication initiative based in Canada during an earthquake event. This is the first study that provides answers to the 10 significant questions.

- What are the common misconceptions?

- What are the root causes of the misconceptions?

- Where can I find evidence of these misconceptions?

- How are these misconceptions produced and reproduced?

- What are some of the tools that would make these misconceptions transparent to learners and educators?

- What are some of the strategic ways to think about addressing misconceptions from a local-national-global perspective?

- What literature will help provide some of these answers?

- What conceptual tools, frameworks, guidelines might be helpful?

- What recommendations might be offered to assist a new EEW?

- What should be avoided in addressing these misconceptions?

To answerer these questions, the E3 Sociocultural Research Project directly takes on three significant challenges: 1) acknowledging the electronic Word of Mouth (eWOM) local-national-global networks are sharing content; 2) moving through the notion that social media and user-created online content is problematic and 3) establishing the science communication context of the new EEW. A meta-analysis of the literature informed our developing innovative rubrics.

The investigation has identified that the global earthquake science ecosystem makes the new EEW system vulnerable to common misconceptions in several different ways.

- Stakeholders and learners face difficulties accessing earthquake science content relevant to the new EEW system.

- Pedagogical content relevant to EEW is rare.

- Marginalised learners are facing difficulties accessing earthquake science content relevant to EEW.

- Methodological errors are evident in the earthquake science content being posted online.

- The literature has the tendency to not make transparent methodological errors in earthquake science communication. This is a requirement to ensure that the content is relevant to the success of a new EEW system.

- Electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) local, national, and global networks are sharing content that is incorrect.

Recognising that context matters, we have focussed the E3 sociocultural project to create a 7-point plan (E3 7-Point Plan) for the Canadian context. The objective is to improve the earthquake science literacy of Canadians in the present and the future. The questions posed in the E3 7-point plan are aimed to close the gaps between: 1) the individual seeking earthquake science; 2) the national initiative of the EEW system implementation and 3) the information available on the world wide web (De Jong, 2024e).

2.3.5 The art of earthquake intensity and earthquake magnitude: A research-based checklist for critique of visual content

This sociocultural research project has developed an instrument to guide the development and critique of earthquake science for EEW system instructional visuals. The tool derives from a synthesis of relevant interdisciplinary literature translated into recommendations for practice. Although a large body of literature exists within science communication, crisis communication, operations research in education, and education psychology to inform the selection of instructional visuals, this literature is dispersed across many fields, journals, and disciplinary traditions. The practical earthquake science lessons are not readily accessible to readers, and available content to support and develop EEW system alert-ready skills are absent from these lessons. To illustrate, humans portrayed as capable of making technical judgements, applying active and mature reasoning and knowledge, engaging in proactive action, and preventing danger, death, or injuries where proactive skills are needed to respond to EEW system alerts are absent.

2.3.6 The seven point plan anchoring magnitude and intensity concepts

This research project showcases the research and analytical work completed to directly address significant research challenges encountered in the sociocultural research. The Earthquake Early Warning Education (E3) 7-point plan (E3 7-Point Plan) provides stand-alone theory for public preparedness education in earth science education, focusing on the learning context. The questions posed in the E3 7-Point Plan close the gaps between the individual seeking earthquake science, the national initiative of the EEW and the information available on the World Wide Web. The research spans STEAM fields, journals, disciplinary traditions. Building the E3 7-Point Plan provided a systematic way to gather different lessons from the literature and apply them to the project. The E3 7-Point Plan pays particular attention to the question of how the new EEW can meet the information needs of the Canadian work force and the disaster risk science community. The purpose of this sociocultural research seeks to ensure the EEW has some of the relevant sociocultural and legal-political information to consider options to address misconceptions now and in the future.

Recommendations and Strategies Derived from the Research

Based on our research, developments, and analyses about these concepts within the public sphere, we outline the following recommendations and strategies for educating the public and enhancing the likelihood they will take appropriate protective actions upon experiencing an EEW alert.

- There needs to be an effort, at least at the national level (but international would be preferable) to standardize these concept definitions within the public discourse. This could include:

- Surveying all government websites to align them with each other. This way people are receiving the same message.

- We are providing several tools and techniques (De Jong, de Jong 2024 b, 2024c,) for critique of visual content to aid in this task

- A more purposeful and consistent implementation of seismic science education in p-K–12 schools across Canada.

- Develop a standardized illustrated intensity chart and post in all public spaces in areas prone to earthquake hazards.

- Understand that the main purpose of the EEW alert is to influence the mindset of the receiver of the alert. Just having a message of what to do is not enough to initiate appropriate protective actions. Therefore, there should also be:

- Government (federal and provincial) initiated PSAs concerning earthquake hazards, the EEW system, how to prepare for such a hazard (what to pack in a hazard kit), and what to do when receiving an alert or experiencing an earthquake.

- Programs that include annual earthquake hazard drills in schools and other public spaces, like the Great ShakeOut.

- Embed foresight principles and standards to meet the needs of the future labour force.

- Design targeted content relevant to the EEW driven by visual design specialists and preparedness educators applying a pedagogical perspective, not public relations and communications perspective.

- Sharpen the focus on the eLearning context and earthquake science communication relevant to EEW.

- Address misinformation/disinformation classification problems with a pedagogical perspective and nurture opportunities to publicly interrogate errors in earthquake science, thereby benefit the new EEW with a presence within user generated content (online networking such as LinkedIn, or other social media platforms, see example of Philippines Institute of Volcanology and Seismology).

- Participate in the electronic Word of Mouth (eWOM) local-national-global networks sharing content.

- Embed foresight principles into the structure and ecosystem of the EEW advice for disaster risk reduction. Consider how principles and standards could provide a systematic and forward approach to addressing some of the challenges the EEW system will face in future years.

Acknowledgements

We would not have been able to complete the research with the quality that we did if it were not for the contributions of so many people and organizations. We would like to thank Natural Resources Canada for their generous funding and make the project a reality, and especially Alison Bird at NRCan, for her unwavering support, ideas, and answering emails almost as fast as I could send them. We would also like to thank contributors and collaborators who gave of their time and knowledge to help push us in productive directions. Dr. Danielle Sumy (National Science Foundation) for her foresight to instigate this project and her insights influencing its direction; Michael Hubenthal (EarthScope) for his research contributions, comments, and advice; Dr. Sarah McBride (USGS) for giving us a forum with the Social Sciences Working Group, and for her valuable feedback. This work would not have been possible without the time and reflection provided by the Pan Canadian survey respondents, our translators, Canadian geoscience educators and Canadian disaster risk management community, especially our French speaking key informants living in earthquake prone locations in Quebec.

References

Allchin, D. (2011). The Minnesota case study collection: New historical inquiry case studies for nature of science education. Science & Education, Published on-line http://www.springerlink.com/content/v42561276210585q/(accessed 1 March 2012), 1–19.

Amin, T. G. (2015). Conceptual metaphor and the study of conceptual change: Research synthesis and future directions. International Journal of Science Education, Downloaded from internet: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2015.1025313, 15 April 2015. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2015.1025313

Aoi, S., Asano, Y., Kunugi, T., Kimura, T., Uehira, K., Takahashi, N., . . . Fujiwara, H. (2020). MOWLAS: NIED observation network for earthquake, tsunami and volcano. Earth, Planets and Space, 72(1), 126. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-020-01250-x

Beger, A., & Smith, T. H. (2020). Introduction. In A. Beger & T. H. Smith (Eds.), How metaphors guide, teach, and popularize science (pp. 1–40). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Bellizzi, J. (2023). Public perception and experiences with earthquake early warning systems and how they impact behavior during earthquakes. University of Calgary.

Clark, A. (2011). Supersizing the mind:Embodiment, action, and cognitive extension. Oxford University Press.

Clement, J. J. (2008). Creative model construction in scientists and students: The role of imagery, analogy, and mental simulation. Springer.

Conant, J. B. (1947). On understanding science: An historical approach. Yale University Press.

De Jong, S. V. Z. (2024a). Answers to 10 significant questions about common misconceptions o f earthquake intensity and earthquake magnitude. University of Calgary.

De Jong, S. V. Z. (2024b). Conclusions and recommendations: Promoting e arthquake magnitude and earthquake intensity in preparedness education. University of Calgary.

De Jong, S. V. Z. (2024c). E3 sociocultural project conclusions and recommendations: Promoting earthquake magnitude and earthquake intensity in preparedness education. University of Calgary.

De Jong, S. V. Z. (2024d). Global visual inventory of earthquake science education: Recommendations for guidelines, templates, and protocols. University of Calgary.

De Jong, S. V. Z. (2024e). The art of earthquake intensity and earthquake magnitude: A research-based checklist for critique of visual content (Earthquake Early Warning Education (E3) Sociocultural Project: Recommended Education 4.0. Strategies, Issue.

De Jong, S. V. Z. (2024f). The seven point plan a nchoring magnitude and intensity concepts: A research-based framework to address misconceptions in earthquake science. University of Calgary.

De Jong, S. V. Z., & Dolphin, G. (2023). Earthquake early warning education (E3), bilingual, trans Canadian sociocultural survey. University of Calgary.

Dolphin, G., & Benoit, W. (2016). Students' mental model development during historically contextualized inquiry: How the 'tectonic plate' metaphor impeded the process. International Journal of Science Education, 38(2), 276–297.

Dolphin, G., Benoit, W., Burylo, J., Hurst, E., Petryshen, W., & Wiebe, S. (2018). Braiding history, inquiry, and model-based learning: A collection of open-source historical case studies for teaching both geology content and the nature of science. Journal of Geoscience Education, 66(3), 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/10899995.2018.1475821

Droboth, J., & Dolphin, G. (2024). Using USGS 'Did You Feel It' responses to understand lived earthquake experiences. University of Calgary.

Given, D., Allen, R. M., Baltay, A. S., Bodin, P., Cochran, E. S., Creager, K., . . . Yelin, T. S. (2018). Revised technical implementation plan for the ShakeAlert system—An earthquake early warning system for the West Coast of the United States [Report](2018-1155). (Open-File Report, Issue. U. S. G. Survey. https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/ofr20181155

Hajar, A. (2021). Theoretical foundations of phenomenography: a critical review. Higher Education Research & Development, 40(7), 1421-1436. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1833844

Herreid, C. F. (2007). Start with a Story: The Case Study Method of Teaching College Science. NSTA Press.

Hodges, L. C. (2005). From problem-based learning to interrupted lecture: Using case-based teaching in different class formats. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education, 33(2), 101–104.

Jones, E. (ND). East vs West Coast Earthquakes. In (pp. Map of USGS “Did You Feel It?” data shows that earthquakes east of the Rocky Mountains are felt over larger areas than earthquakes in the West.). usgs.gov: United States Geological Survey.

Kilb, D., Bunn, J. J., Saunders, J. K., Cochran, E. S., Minson, S. E., Baltay, A., . . . Kodera, Y. (2021). The PLUM Earthquake Early Warning Algorithm: A Retrospective Case Study of West Coast, USA, Data. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 126(7), e2020JB021053. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JB021053

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1999). Philosophy in the flesh: The embodied mind and its challenge to western thought. Basic Books.

Latour, B. (1987). Science in action: How to follow scientists and engineers through society. Harvard University Press.

Matthews, M. M. (2015). Science Teaching: The Contribution of History and Philosophy of Science, 20th Anniversary Revised and Expanded Edition. Routledge.

McBride, S. K., Bostrom, A., Sutton, J., de Groot, R. M., Baltay, A. S., Terbush, B., . . . Vinci, M. (2020). Developing post-alert messaging for ShakeAlert, the earthquake early warning system for the West Coast of the United States of America. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 50, 101713. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101713

Muturi, E., & Dolphin, G. (2024). I feel the earth move under my feet: The history of earthquake intensity and magnitude. University of Calgary.

Neisser, U. (1976). Cognition and Reality: Principles and Implications of Cognitive Psychology. W.H. Freeman and Company.

Niebert, K., & Gropengiesser, H. (2015). Understanding starts in the mesocosm: Conceptual metaphor as a framework for external representations in science teaching. International Journal of Science Education, 37(5–6), 903–933. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2015.1025310

Rehorick, D. A. (1986). Shaking the Foundations of Lifeworld: A Phenomenological Account of an Earthquake Experience. Human studies, 9(4), 379-391. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00143171

Riddell, G. A., van Delden, H., Maier, H. R., & Zecchin, A. C. (2020). Tomorrow's disasters – Embedding foresight principles into disaster risk assessment and treatment. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 45, 101437. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101437

Shapiro, L. (2011). Embodied cognition. Routledge.

Sheridan, M. B. (8 September 2021). Mexicans clean up after powerful earthquake rattles Acapulco and Mexico City. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/09/07/mexico-earthquake-7-ucgs/

Statewide California Earthquake Center. (2024). Great Shakeout Earthquake Drills. Retrieved 26 March 2024 from https://www.shakeout.org/index.html

Stokes, A. (2011). A phenomenographic approach to investigating students' conceptions of geoscience as an academic discipline. In A. D. Feig & A. Stokes (Eds.), Qualitative inquiry in geoscience education research: Geological Society of America Special Paper 474 (pp. 23–35). Geological Society of America.